Results

Phage Spotting

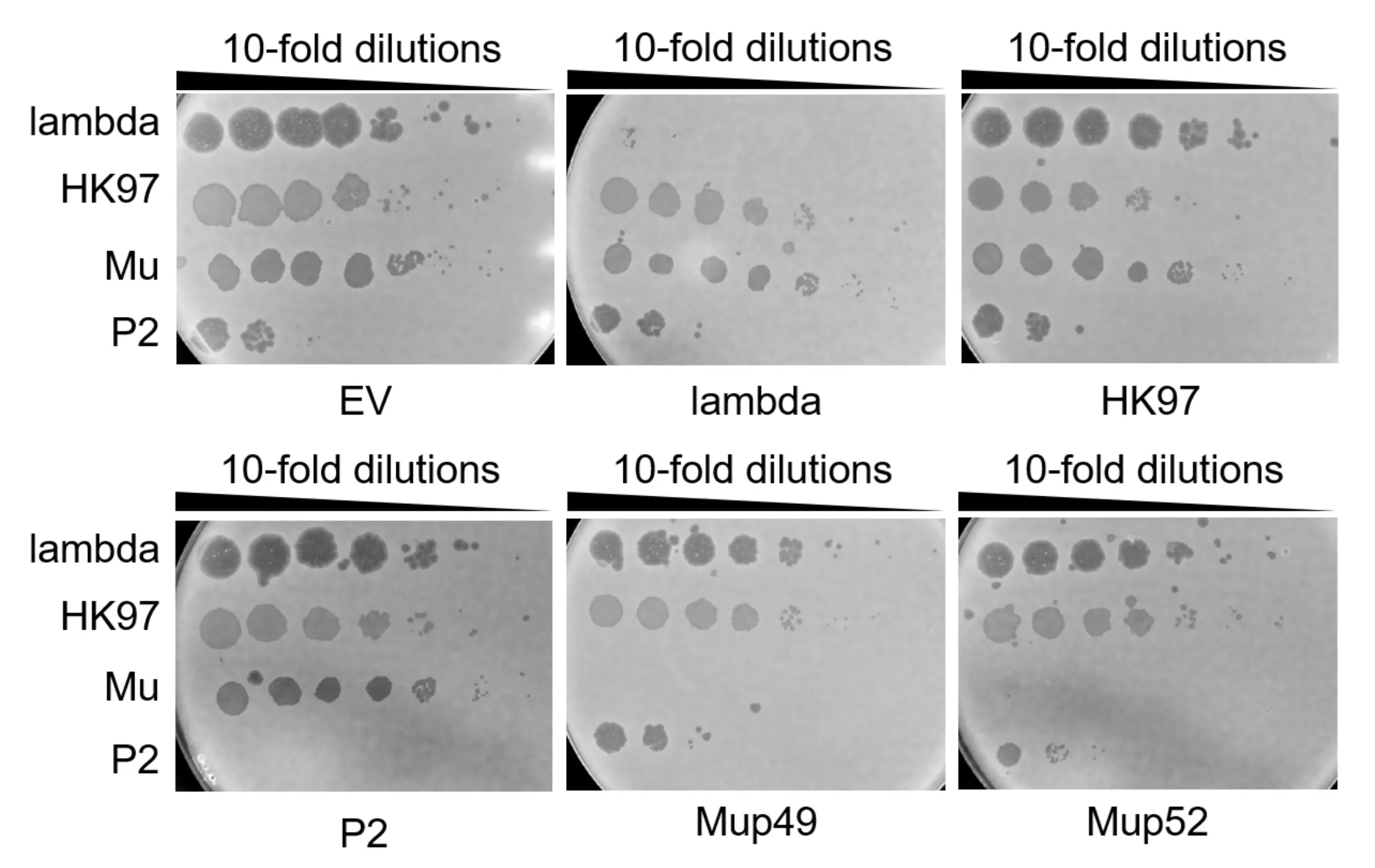

To validate the phage–host receptor panel used in downstream experiments, we performed phage spotting assays in which Lambda, HK97, P2 and Mu were spotted onto E. coli strains that differ only in outer-membrane receptor or LPS composition. In this spot assay, small volumes of phage lysate are applied to a confluent bacterial lawn and lytic infection produces clear zones (plaques) where bacteria are killed; the presence, number, and size of plaques reflect phage infectivity on that host. Each phage was tested on its cognate target strain and on control strains lacking the presumed receptor (ΔLamB or ΔOmpC) or expressing a truncated R1 LPS.

The results in Fig. 1 below confirm the expected phenotype – the WT protein-binding phages (Lambda and HK97) have high spotting efficiency towards the LamB receptor (ΔOmpC) and none towards OmpC receptor (ΔlamB), and the WT glycan-binding phages (P2 and Mu) have high spotting efficiency towards the K12 LPS and much less so towards the truncated R1 LPS. This validates our positive control for the phage spotting, and that these receptor types are suitable for examining how RBP swapping might change host specificity.

The wild-type protein binding phages Lambda and HK97 had high spotting efficiency in the OmpC knock-out E. coli, and low efficiency in lamB knock-out E. coli. Similarly, the wild-type glycan-binding phages P2 and Mu had high spotting efficiency in E. coli expressing the K12 LPS, and low efficiency against E. coli expressing the truncated R1 LPS.

sgRNA Validation

To assess activity of candidate single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs) against our phages, we performed Cas-dependent plaque-reduction spot assays. Bacterial lawns were co-transformed with tCas9 or I-C plasmids expressing a Cas protein and either a sgRNA or an empty sgRNA cassette (empty vector, EV). The tCas9 plasmid expresses S. pyogenes Cas9, regulated by the arabinose-inducible PBAD promoter. I-C expresses a cascade (multiprotein complex) comprised of Cas5c, Cas7c, Cas3, and Cas8c proteins. Expression is regulated by the rhamnose-inducible promoter system (RhaSR-PrhaBAD).

Upon Cas-protein induction, a functional sgRNA was expected to prevent plaque formation by its cognate phage while leaving non-target phages unaffected. Results and interpretation of these assays is shown in Figs. 2 and 3 below.

P2 phages were spotted on E. coli K12, which were transformed with tCas9, which inducibly expresses Cas9, and either a sgRNA for a specific phage or an empty sgRNA cassette (empty vector, EV). We expect plaque formation in all conditions (uninduced P2 EV, P2-1; induced P2 EV) except for induced P2-1, where Cas9 is expressed and the sgRNA is present.

P2, Mu, and HK97 phages were spotted on E. coli K12, which were transformed with the pCas3Rh plasmid, which inducibly expresses the Type I-C CRISPR-Cas components and either a sgRNA for a specific phage or an empty sgRNA cassette (empty vector, EV). We expect plaque formation in all uninduced and EV conditions. When Cas expression is induced and the sgRNA is present, we expect reduced plaque formation. Note: Mup49 and Mup52 refer to two different RBDs for the Mu phage.

Plaques were smaller and fainter in Cas-induced and sgRNA-present conditions than EV or uninduced conditions in both tCas9 and IC plasmid systems, indicating that Cas expression and sgRNA targeting may have partially interfered with phage replication. However, the spotting efficiency was lower than the average spotting efficiency for all phages overall for all conditions, including controls. This suggests that the bacteria are behaving abnormally under induction conditions, since we expect robust plaque formation in uninduced and empty-vector controls.

The inconsistent results from tCas9 and IC plasmids prompted us to test other Cas-protein and sgRNA expression vectors, leading us to select pCas9 and pCRISPR. pCas9 expresses S. pyogenes Cas9 (SpyCas9) under a constitutive promoter, and pCRISPR is a compatible sgRNA expression plasmid with an independent origin of replication and antibiotic resistance marker. The results of the subsequent testing are shown in Figs. 4 & 5 below.

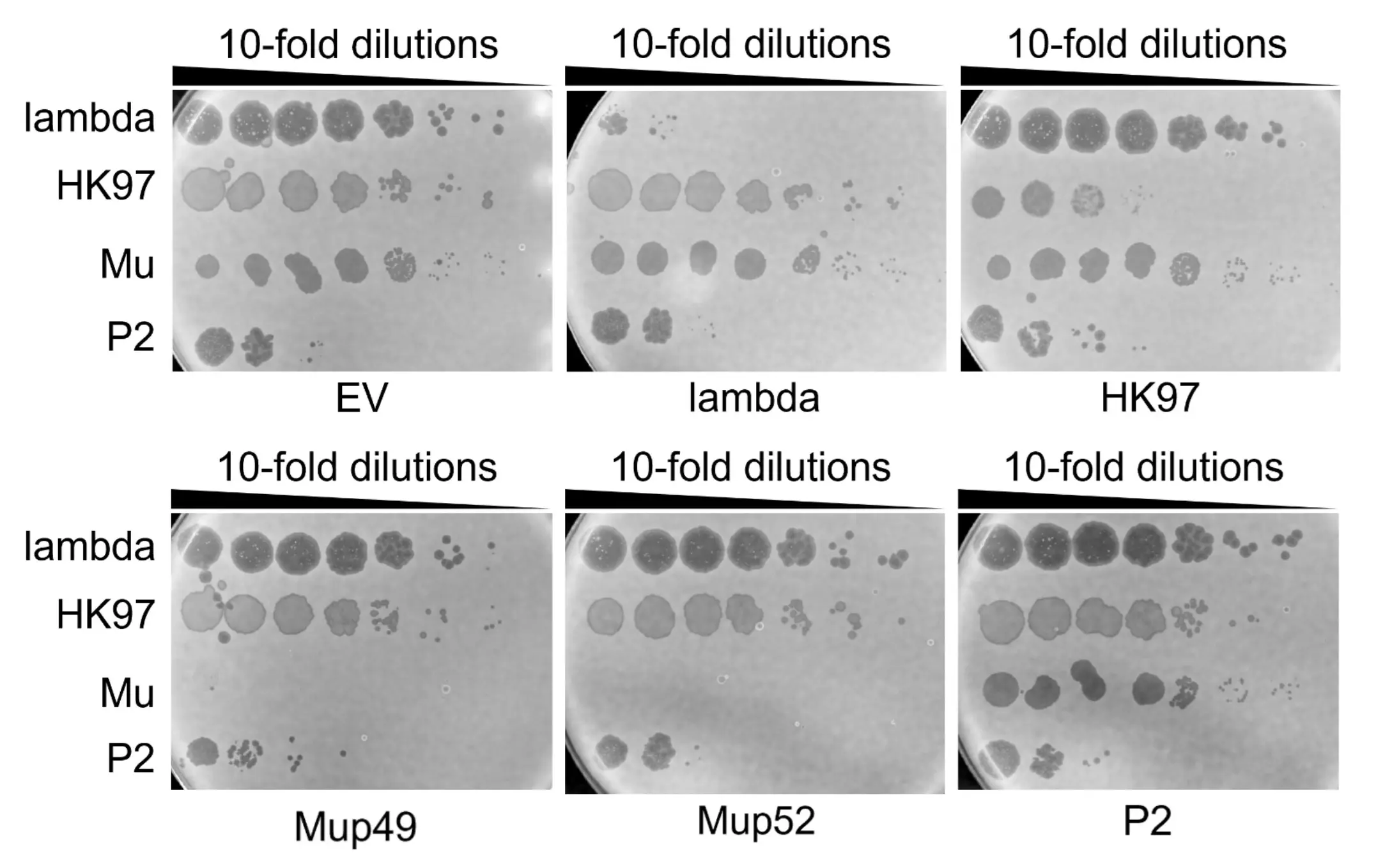

Lambda, HK97, P2, and Mu phages were spotted on E. coli K12, which were transformed with pCas9 expressing Cas9, and either a sgRNA for a specific phage or an empty sgRNA cassette (empty vector, EV). We expect all phages to form plaques except for the phage being targeted by the gRNA. Mup49 & Mup52 are used to denote two different RBDs of the wild-type Mu phage. Results indicate that all sgRNAs did not inhibit plaque formation.

In a subsequent experiment, pCas9 was co-transformed with another plasmid, pCRISPR, in E. coli K12; here, the plasmid expressing Cas machinery was separated from the sgRNA expression vector, shown in Fig. 5 below.

Lambda, HK97, P2, and Mu phages were spotted on E. coli K12, which were co-transformed with pCas9 (expressing Cas9 with an empty sgRNA cassette) and either pCRISPR with a sgRNA for a specific phage or an empty sgRNA cassette (empty vector, EV). We expect all phages to form plaques except for the phage being targeted by the sgRNA. Mup49 & Mup52 are used to denote two different RBDs of the wild-type Mu phage. Positive control 1 and 2 are sgRNA targeting K12 that were previously validated in the Davidson Lab. Results indicate that all sgRNAs did not inhibit plaque formation. However, since positive controls 1 & 2 also did not show reduction in plaque formation, we interpret this as systemic error in the experimental setup, which leads us to new avenues for troubleshooting.

These data indicate that while native phage-receptor interactions were robustly validated, with protein-binding (Lambda, HK97) and glycan-binding phages (P2, Mu) showing the expected host-range patterns, the CRISPR-Cas interference assays did not provide reproducible evidence of sgRNA-mediated phage inhibition. Inducible tCas9 and Type I-C systems produced smaller, fainter plaques under induction yet showed low overall spotting efficiency and loss of expected control phenotypes, implicating induction conditions, plasmid burden, or other systemic experimental error. That compromised bacterial or phage fitness. As a result, we moved to a constitutive pCas9/pCRISPR configuration to decouple Cas and sgRNA expression and minimize confounding effects; further investigation will be required to conclusively evaluate sgRNA activity.

Gibson assembly of dry lab-generated RBDs

Gibson assembly for the dry lab’s first batch of Mu and P2 RBDs was validated by Sanger sequencing.

sgRNA Troubleshooting

We are in the process of troubleshooting our sgRNAs, this time examining fundamental parts of our experimental design (such as the types of E. coli K12 strains we are using) to see where errors might be occurring. We suspect there might be issues with our bacterial strain having natural chloramphenicol resistance, which would prevent it from uptaking the pCas9 plasmid. By investigating these issues and making necessary troubleshooting steps, we hope to have working sgRNAs in the coming weeks.

Gibson Assembly of New RBD Batches

At the time of writing this wiki, we are in the process of ordering and receiving new batches of RBDs — batch 1 of generated HK97 and Lambda RBDs (arrived), and batch 2 of generated Mu and P2 RBDs (to be ordered). Using existing primers we previously ordered, we are ready to complete Gibson Assembly to clone these RBDs into pETDuet-1.

We will confirm successful Gibson Assembly of the new RBDs into pETDuet-1 by Sanger sequencing.

Recombination of RBDs Using Validated sgRNAs

Immediately following successful sgRNA validation, we will proceed with recombination of our cloned RBDs into lysogenic E. coli K12, validating successful swaps via colony PCR with checking primers. Afterwards, we will conduct the same phage spotting assay shown in Fig. 1, this time with the mutant phages (and wild types as controls). We are working to complete these experiments in the coming weeks.

Immediate Future Experiments

To characterize generated RBDs that enable successful phage targeting of the above bacterial receptors, we will employ adsorption and growth curve assays. These serve to characterize the results of the spotting assay in two ways. First, the adsorption assay interrogates the binding efficiency of the native and designed RBDs to the bacterial receptor it targets. The growth curve quantifies the phage spotting assay using phage titres, allowing for an objective assessment of lytic efficiency of the bacteriophage of interest. A one-step growth curve is achieved by inoculating a sensitized bacterial culture with the phage of interest and sampling the culture at various time-points to perform a plaque assay, through which the changes in phage titres can be quantified and plotted over the infection time[1].

Future Directions in Phage RBD Discovery and Optimization

Advances in structural biology will be critical once a working AI-designed RBD is identified. Cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) is especially well-suited to phage tail complexes because it requires no crystals and can image very large assemblies in a near-native state. Recent cryo-EM studies routinely achieve near-atomic resolution on whole phage particles and tail fibers[2]. X-ray crystallography, by contrast, can deliver the highest atomic detail for isolated RBP domains (especially rigid tailspikes), yielding clear structures of the binding interface[2]. In practice one would use both: cryo-EM on the intact phage (or tail complex) to visualize overall architecture and cryo-electron tomography (cryo-ET) for in situ context, while X-ray diffraction of purified RBD or tailspike fragments provides high-resolution models of the receptor-binding site[2]. Together these structures (“blueprints”) help explain how the RBD docks to its receptor and guide further model design and engineering.

Post Wiki Freeze Results

This section details all results the iGEM Toronto 2025 team achieved in between the 2025 wiki freeze and 2025 wiki thaw deadlines.

sgRNA Validation Update

Natural chloramphenicol resistance in the E. coli K-12 was believed to have contributed to the error in the prior sgRNA validation experiment. A non-ampicillin resistant strain was therefore grown and used in the re-run of the sgRNA validation experiment. Once again, K-12 bacterial cells were transformed with two plasmids, one containing pCas9 and the other containing either an empty vector (EV) or the sgRNA specific to a target phage (Lambda, HK97, P2, Mup49, and Mup52). Lambda, HK97, Mu, and P2 WT phages were then spotted onto each of the K-12 transformed conditions. The results of the sgRNA validation re-run are shown in Fig. 6 below.

Lambda, HK97, P2, and Mu phages were spotted on E. coli K12, which were co-transformed with pCas9 (expressing Cas9 with an empty sgRNA cassette) and either pCRISPR with a sgRNA for a specific phage or an empty sgRNA cassette (empty vector, EV). We expect all phages to form plaques except for the phage being targeted by the sgRNA. Mup49 & Mup52 are used to denote two different RBDs of the wild-type Mu phage. Results indicate that sgRNAs targeting Lambda, P2, Mup49, and Mup52 successfully inhibit plaque formation. These sgRNAs show no detectable off-target activity against non-target phages, as indicated by their spotting efficiency being maintained.

As seen in the phage spotting results, the sgRNAs designed for each WT phage effectively attenuated production of their respective targets. Splitting the pCas9-sgRNA system across two plasmids, however, can lead to stoichiometric imbalance, reducing the consistency of phage-spotting experiments with engineered phages that require tightly controlled counter-selection. Another sgRNA targeting experiment was therefore performed to test the efficacy of a single-plasmid system (using pCas9), the results of which are shown in Fig. 7 below.

Lambda, HK97, P2, and Mu phages were spotted on E. coli K12, which were co-transformed with pCas9 expressing both Cas9 and an sgRNA cassette or pCas9 with an empty sgRNA cassette (empty vector, EV). We expect all phages to form plaques similarly to what was observed in Fig. 6. Mup49 & Mup52 are used to denote two different RBDs of the wild-type Mu phage. Results indicate that sgRNAs targeting Lambda, Mup49, and Mup52 successfully inhibit plaque formation. These sgRNAs show no detectable off-target activity against non-target phages, as indicated by their spotting efficiency being maintained.

The overall pattern mirrors that of the dual-plasmid results; however, the Lambda and P2 sgRNA-pCas9 constructs were less effective at attenuating their respective phages in this single-plasmid system.

RBD Swapping Update

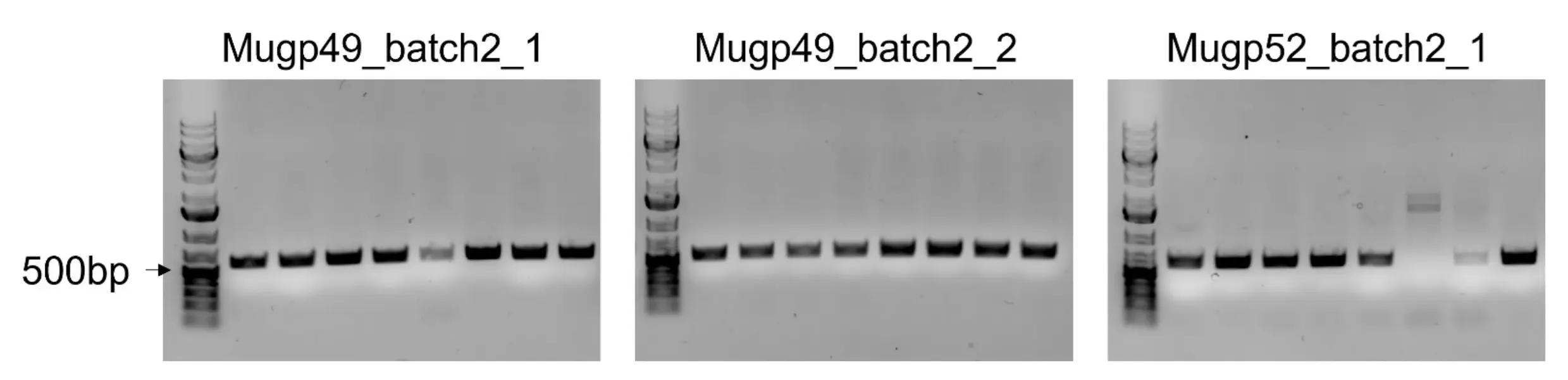

To replace the WT phage RBD with our AI-generated variants, we used homologous recombination coupled with CRISPR-Cas9 counterselection. To enhance recombination efficiency, we employed the lambda-Red recombination system (which represented a change in our original HDR-like recombination strategy at the time of the wiki freeze, due to its low efficiency). Linear dsDNA fragments containing the AI-generated RBDs flanked by homology arms, together with the pCas9 plasmid carrying the appropriate sgRNAs, were transformed into the Mu lysogen (E. coli K-12 containing a Mu prophage) harboring the lambda-Red plasmid. Following transformation, cells were selected on chloramphenicol to maintain the pCas9 plasmid. After CRISPR selection, we screened for successful RBD recombinants using colony PCR. One primer was designed to bind outside the homology arm region in the K-12 lysogen genome, and the other was located within the engineered RBD sequence. By designing one primer to bind outside the engineered RBD, we ensured that PCR amplification would confirm both the presence of the correct engineered sequence and its successful integration at the correct genomic location. A ~600 bp PCR product should therefore be produced only in the positive recombinant cells but not any WT cells.

Using this pipeline, we successfully swapped the wild-type RBD in Mu with Mugp49_batch2_1, Mugp49_batch2_2, Mugp52_batch2_1, and Mugp52_batch2_2 (which were four of the nine RBDs the dry lab team produced in their second batch). For each construct, eight colonies were tested, and all were positive except for one colony from the Mugp52_batch2_1 swap (Fig. 8). This colony may have carried a mutation in the PAM or protospacer region that enabled escape from CRISPR selection.

Primers specifically designed to amplify replaced (swapped) RBDs in the E. coli K-12 lysogen were used in colony PCR. Amplicons were then run on an agarose gel to inspect their size. All colonies with a band size of ~600 bp were denoted as successful recombinants, while colonies without this correct band size were not proceeded with. Note: Mugp52_batch2_2 colony PCR gel image is not shown.

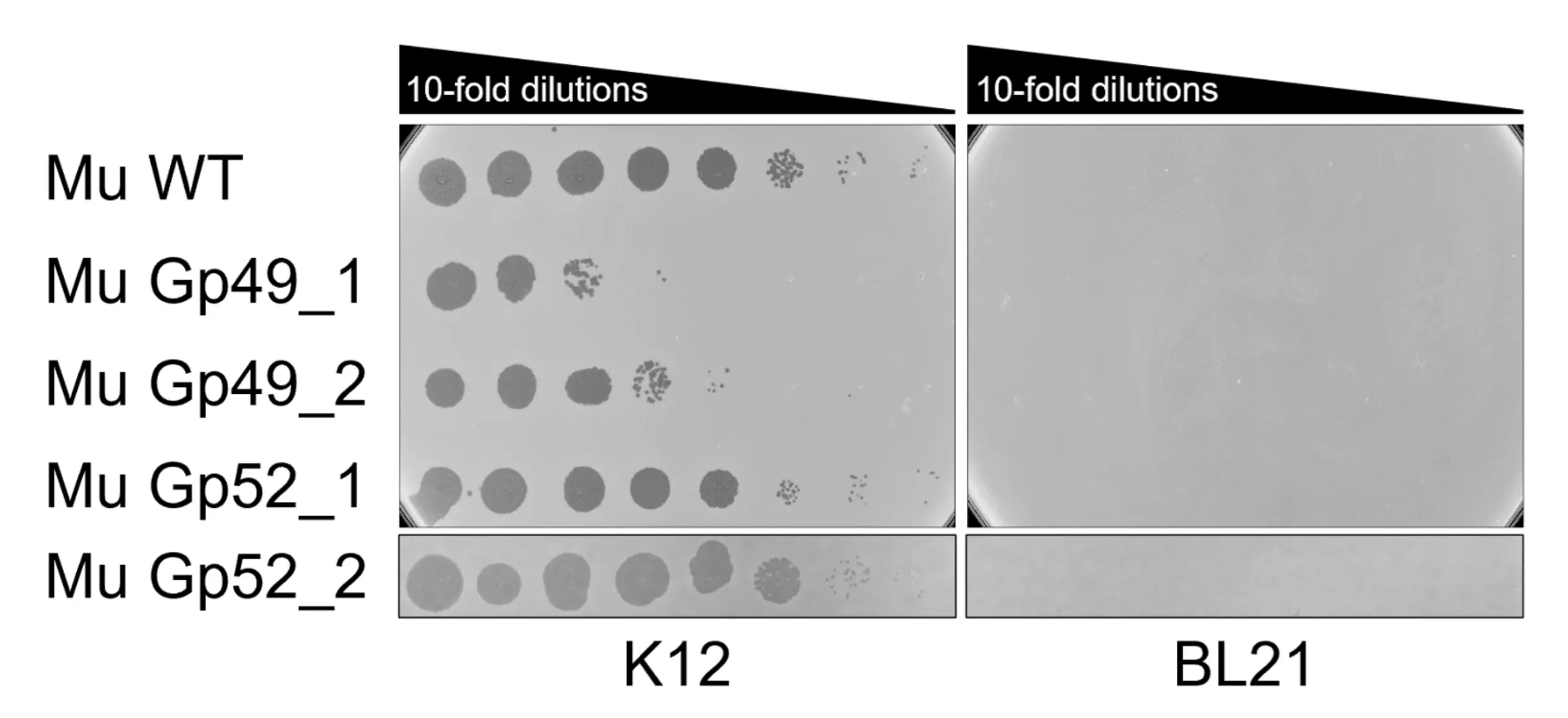

RBD Screening Update

To evaluate whether the AI-generated RBDs alter host specificity, we examined the recombinant phages on E. coli K-12 and BL21. Wild-type Mu infects K-12 but not BL21. Mu encodes two RBPs, gp49 and gp52, arranged in opposite orientations on a spontaneously reversible operon, and only one RBP is expressed at a time. As a result, lysates induced from a Mu lysogen contain a mixed population of gp49- and gp52-displaying phages at approximately a 1:1 ratio. Because only one of the two RBDs is replaced in each engineered phage, roughly half of the virions should still retain the wild-type RBD capable of infecting K-12. Thus, loss of K-12 infectivity is not expected. However, any gain of infectivity on BL21 would indicate that the AI-generated RBD can recognize a BL21 receptor. Despite this, none of the engineered RBDs tested so far have conferred infectivity toward BL21 (Fig. 9).

Mu phages swapped with Mugp49_batch2_1 (Mu Gp49_1), Mugp49_batch2_2 (Mu Gp49_2), Mugp52_batch2_1 (Mu Gp52_1), and Mygp52_batch2_2 (Mu Gp52_2) were spotted on E. coli K-12 and E. coli BL21. All phages spotted on K-12, but did not display any gain of infectivity for BL21.

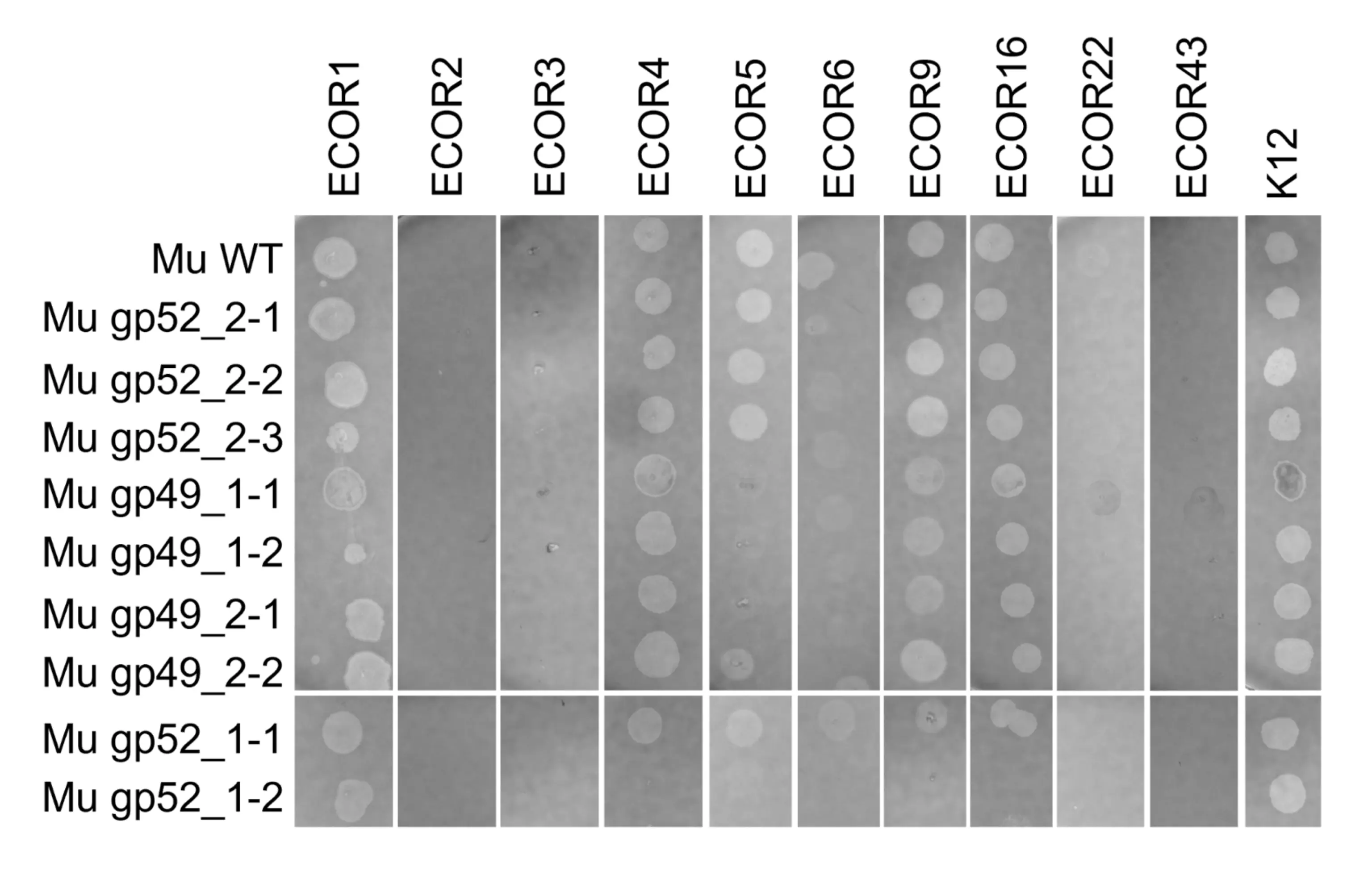

Because none of the tested RBDs gained infectivity toward BL21, we next examined whether they might confer infectivity on other E. coli strains. We selected 10 strains from the ECOR collection, each representing one of the five major outer‑core LPS types found in E. coli: K‑12, R1, R2, R3, and R4. Two strains were chosen from each group: ECOR2 and ECOR3 (K‑12), ECOR16 and ECOR22 (R1), ECOR1 and ECOR5 (R2), ECOR6 and ECOR9 (R3), and ECOR4 and ECOR43 (R4) [3]. Notably, strains within the same LPS outer‑core group can still differ in their O‑antigen composition, meaning their surface receptors are not identical. To account for potential variation among recombinant colonies, we tested two to three independent positive recombinants for each AI‑generated RBD (indicated by the -1/2/3 prefix at the very end of the mutant phage name in Fig. 10 below). Because failure of receptor binding results in complete absence of plaques even at the lowest dilution, we screened only undiluted lysates for efficiency. Any plaque formation on strains that wild‑type Mu cannot infect would indicate that an AI‑generated RBD had expanded the host range. However, no such infectivity was observed for any engineered RBD (Fig. 10).

Two to three clones of four mutant phages with AI-generated batch 2 RBDs (Mu gp49_1, Mu gp49_2, Mu_gp_52_1, and Mu_gp 52_2) were screened against the 10 following strains in the ECOR collection to test the specificity of the mutant phages: ECOR2 and ECOR3 (K‑12), ECOR16 and ECOR22 (R1), ECOR1 and ECOR5 (R2), ECOR6 and ECOR9 (R3), and ECOR4 and ECOR43 (R4). We expect that if a mutant phage has gained infectivity for any of the ECOR strains, it will form plaques on that strain while not forming any plaques on K-12. However, no phages display any gain of infectivity.

Future Directions

So far, we have only tested AI‑generated Mu RBDs, and our attempts to engineer RBDs from other phages (HK97, lambda, and P2) were unsuccessful for distinct technical reasons. For HK97, we designed four different sgRNAs targeting the wild‑type RBD, but none produced efficient CRISPR targeting. For lambda, we obtained no colonies after CRISPR counterselection, likely because lambda carries its own endogenous lambda‑Red system, which may have interfered with the lambda‑Red plasmid used to mediate recombination. For P2, CRISPR counterselection yielded colonies, but none were positive recombinants, even after screening with two independent primer pairs. This may reflect differences in recombination efficiency across prophage backgrounds or incompatibilities between the lambda‑Red machinery and the P2 genome. To overcome these limitations, future work will focus on establishing an alternative phage engineering pipeline in yeast. In this system, phage genomes will be recombineered directly in yeast and subsequently rebooted in E. coli. This approach bypasses bacterial recombination constraints and eliminates the need for CRISPR‑based counterselection[4]. Future work will also involve integration of the above wet lab results into the PHORAGER model, potentially through an active learning-like or guided generation strategy.

High-throughput library screening will let us rapidly test thousands or millions of AI-generated RBD variants. For example, one could build a phage- or yeast-display library of RBD sequences and perform iterative “biopanning” rounds against the target bacterium or purified receptor. Phage display leverages extremely diverse libraries (often > 10⁹ variants) and enriches binders through repeated selection rounds, quickly winnowing a huge pool down to a few strong candidates[5]. Coupling this with deep sequencing or high-content sorting allows parallel measurement of many variants’ binding. Approaches like surface plasmon resonance (common in antibody engineering) would let us scan the AI-designed library at scale and pick out functional RBDs for further validation[6].

Finally, directed evolution can refine any hits and generate data to improve the AI model. In practice this might mean taking a promising AI-designed RBD, introducing diversity (e.g., by error-prone PCR, DNA shuffling or mutagenesis plasmids), and then selecting for tighter binding or broader host range over multiple rounds. For example, phage-assisted continuous evolution (PACE) or cyclic error-prone phage propagation could iteratively improve binding affinity and specificity. These methods are analogous to antibody maturation and have been used to expand phage host range by mutating tail fiber proteins[2]. Each round of selection generates new sequence–function data (which RBD mutations enhance binding), which could be fed back to retrain the AI model. In this way, iterative cycles of design → experimental selection → data-driven re-design would converge on optimized RBDs that both work in vitro and enrich the training set for future predictions[2].