Verification of Degradation Module Feasibility

1.Construction of Degradation Enzyme Expression Strains

Using genome editing to construct A MHETase-expressing yeast strain. First, a linear repair

template

containing the MHETase gene was amplified and fused, then integrated into the genome via

CRISPR-mediated

homologous recombination. Subsequently, a plasmid carrying the FAST-PETase gene was

introduced into the

yeast, generating the final degradation enzyme expression strain.

Figure 1. Construction of degradation enzyme expression strains.

A.Design of plasmids and fusion fragments;

B.Gel electrophoresis of the fused MHETase repair template;

C.Plate culture of degradation enzyme expression strains.

2.Verification of Enzyme Expression Strains

First, extract genomic DNA of the recombinant strains. Colony PCR was performed then using

primers

targeting the fusion junctions and degradation enzyme genes, followed by gel electrophoresis

to verify

integration and expression.

Figure 2. Verification of PCR amplified FAST-PETase gene and MHETase fragment junction

by gel

electrophoresis.

Target colonies with correct integration were selected for subsequent experiments.

3.Measurement of Microplastic Degradation Efficiency

TPA, MHET, and BHET standards were mixed in equal ratios to prepare a gradient concentration

mixture.

Retention times were recorded and standard curves was generated via HPLC. The degradation

enzyme

expression strains were cultured in 20 mL of medium containing microplastics for 72 hours.

2mL of

fermentation broth were sampled, processed, and analyzed via HPLC. The chromatographic data

were compared

with standards for quantification.

Figure 3. Quantitative analysis of microplastic degradation using HPLC.

A.Chromatogram of experimental groups, control groups, and standards under 254 nm UV

detection;

B.Standard curve generated from mixed standards;

C.Chromatographic peak areas of degradation products in each group;

D.Calculated concentrations of degradation products based on the standard curve.

The chromatographic data indicated that the degradation enzyme expression strains

effectively degraded PET

microplastic powder.

4.Validation of Glucose-Responsive Logic Gate Promoter

A fluorescent reporter strain was constructed via genome editing by integrating a linear

repair template

carrying HXT1p-EGFP into the yeast genome. Verified colonies were cultured in

media containing

0.1%, 0.2%, and 4% glucose (equal total carbon source) for 24 hours. Fluorescence and OD600

were measured

using a microplate reader to assess glucose-induced expression.

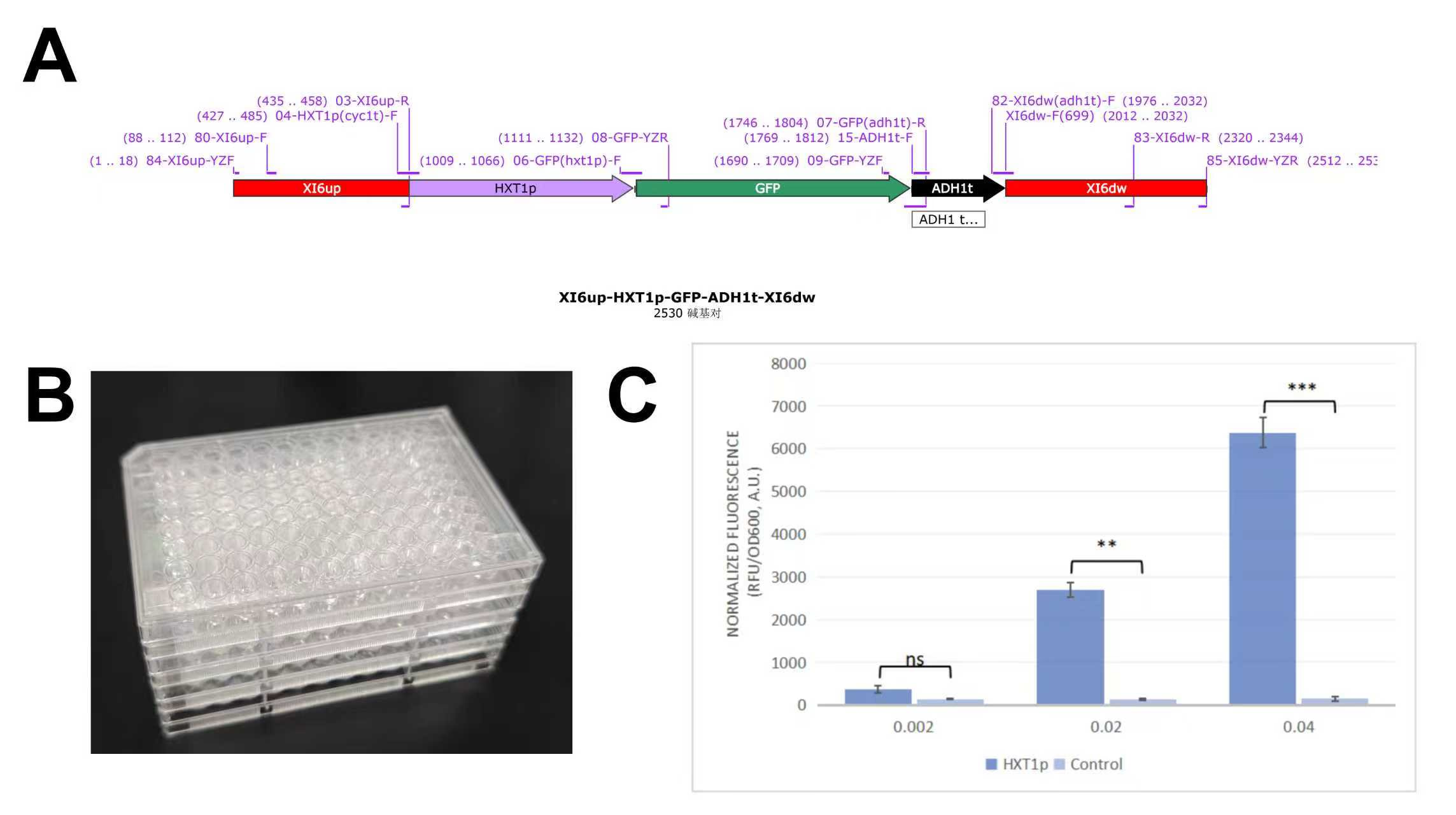

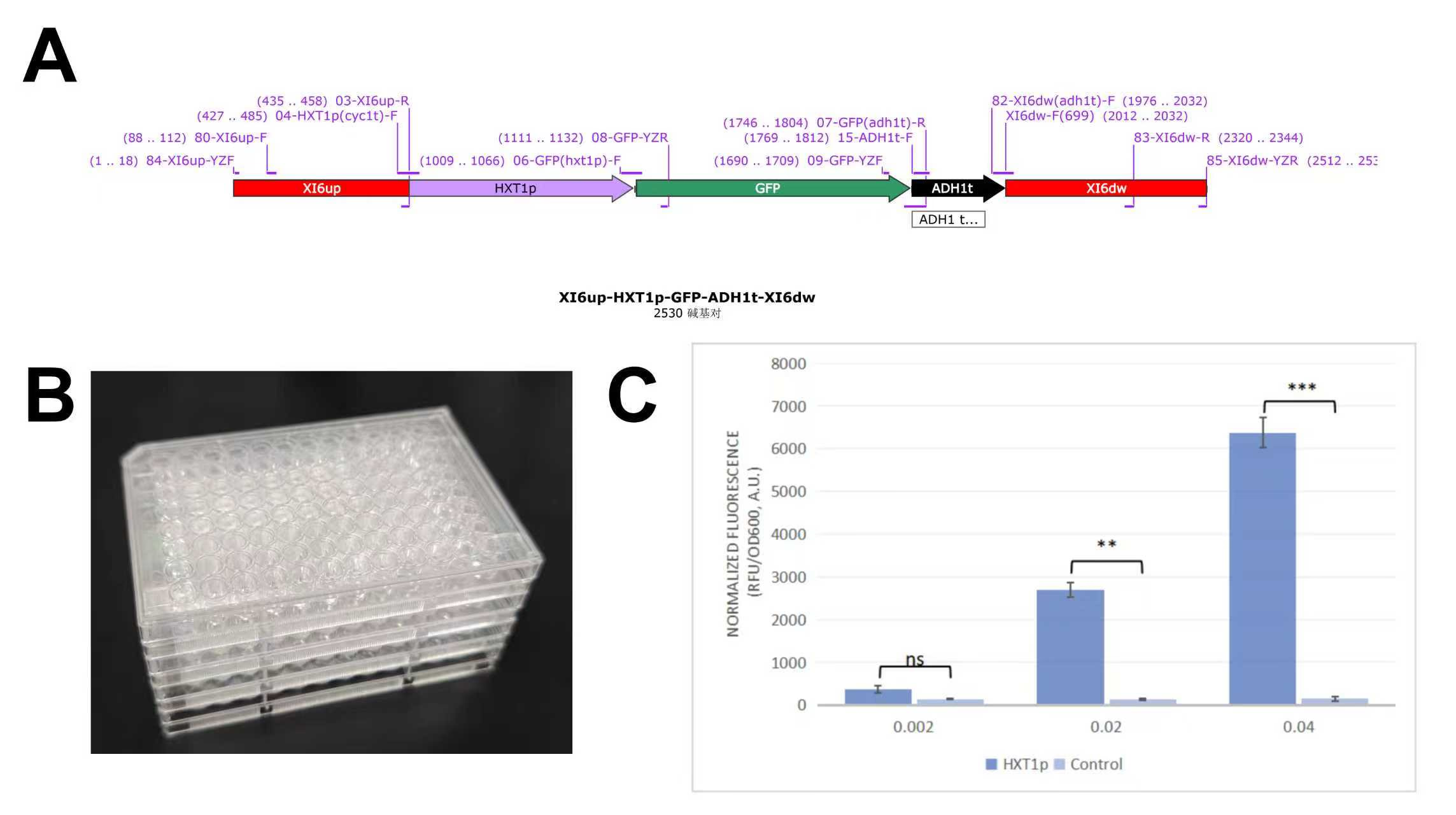

Figure 4. Construction and fluorescence validation of glucose-inducible promoter strain.

A.Design of linear repair template and primers;

B.96-well plate containing experimental cultures;

C.Normalized fluorescence intensity detected by microplate reader.

The data measured by the microplate reader showed that the fluorescence expression activity of the engineered strain increased with the rising glucose concentration. This result demonstrates that the promoter can effectively sense glucose levels and achieve the recognition of feeding signals.

Verification of Adsorption Module Feasibility

1.Prescreening of Surface Display Fusion Proteins

Three linker between HFBI and Aga2, (G4S)3,

(G4S)5, and

(G4S)8, were tested. TMHMM and ProtScale were used to analyze

transmembrane

domains and hydrophobicity. AlphaFold Server was used to predict structural fidelity of

HFBI and Aga2

domains. Docking simulations with PET were performed using AutoDock and visualized in

PyMOL.

Figure 5. Pre-experimental feasibility analysis of HFBI surface display fusion

proteins.

A.Genetic map of HFBI fusion constructs;

B.Analysis of transmembrane structures and hydrophobicity;

C.RMSD-based structural fidelity comparison of fusion proteins;

D.Docking energy analysis of protein-PET interactions.

Results showed all three fusion constructs were feasible for surface display. Constructs

5-1 and 8-1

displayed higher structural fidelity, while 3-1 showed greater deviation. Docking

analysis confirmed

strong PET-binding potential.

2.Design and Construction of Adsorption Module Plasmids

Two plasmids linking AGA2 and HFBI with (G4S)3 and

(G4S)8

were designed and synthesized. The plasmids were transformed into yeast, and colony PCR

was used for

verification.

Figure 6. Construction and preliminary validation of adsorption strains.

A.Designed plasmids;

B.Transformation and plating results;

C.Colony PCR verification.

Gel electrophoresis confirmed correct plasmid integration for subsequent experiments.

3.Validation of Surface Display

To verify V5-tag surface display, yeast cells were harvested, washed, blocked, incubated

with

fluorescent antibody, and mounted in 80% glycerol for confocal microscopy observation.

Figure 7. Confocal microscopy of immunofluorescently labeled adsorption strains.

Confocal imaging revealed orange-red fluorescence in experimental groups but not in

controls, confirming

surface localization of fusion proteins without cell permeabilization.

4.Validation of Adsorption Function

Adsorption strains were cultured in 20 mL of medium containing microplastics for 36

hours. Cells were

collected, washed, embedded, and sectioned for TEM imaging.

Figure 8. TEM observation of microplastic adsorption on yeast cell surfaces.

TEM images showed microplastic accumulation around yeast cells in experimental groups,

but not in

controls, demonstrating effective adsorption capability.

Validation of Anti-inflammatory and Antioxidant Module

1.Construction of ΔSEC72 Strain

A gRNA plasmid targeting SEC72 was designed and assembled via multi-fragment PCR and

one-step cloning.

The plasmid was amplified in E. coli and confirmed by sequencing.

Figure 9. Design, construction, and verification of SEC72-targeting plasmid.

A.Primers targeting SEC72;

B.PCR amplification of gRNA fragments;

C.Recombinant plasmid plating on selective media;

D.Sequencing confirmation.

2.CRISPR-mediated Knockout of SEC72

A linear repair template containing upstream and downstream homologous arms of SEC72

was generated via

overlap PCR. The repair template and gRNA plasmid were co-transformed into yeast to

induce homologous

recombination, followed by colony PCR verification.

Figure 10. Construction of linear repair template and verification of SEC72

knockout.

A.Primer design based on SEC72 flanking regions;

B.PCR amplification of repair template;

C.Colony PCR confirmation of SEC72 deletion.

3.Design and Construction of the Anti-inflammatory and Antioxidant Module

Functional elements were amplified and fused to form a linear repair template,

co-transformed with

gRNA plasmids for CRISPR-mediated genome integration.

Figure 11. Design and construction of the anti-inflammatory and antioxidant

strain.

A.Template and primer design;

B.Homologous recombination to obtain full-length template;

C.Transformation and colony screening.

4.Verification of Constructed Strains

Colonies were expanded briefly, genomic DNA extracted, and colony PCR performed to

identify correctly

constructed strains.

Figure 12. Colony PCR validation of anti-inflammatory and antioxidant strains.

Validation of Safety Modules

1.Alginate-Chitosan Encapsulation for Acid Resistance

To enhance acid tolerance, sodium alginate–chitosan microcapsules were prepared and

tested in

simulated gastric fluid. Free and encapsulated yeasts were incubated for 2 hours,

plated, and analyzed

for survival.

Figure 13. Preparation of microcapsules and validation of acid resistance.

Encapsulated yeast showed high survival rates, while unencapsulated yeast died in

simulated gastric

conditions, demonstrating effective protection.

2.Temperature-Responsive Safety Module

A fluorescent strain carrying HSP26p-EGFP was constructed via CRISPR. Strains were

cultured at 30°C,

37°C, and 42°C for 24 hours, and fluorescence was measured.

Figure 14. Construction and fluorescence validation of temperature-inducible

promoter strain.

A.Design of HSP26p-EGFP template and primers;

B.Colony PCR validation;

C.Fluorescence intensity under different temperatures.

Results showed that HSP26p activity significantly increased at 37°C and 42°C,

confirming its

temperature sensitivity and effective induction.

3.Arabinose-Responsive In Vivo Safety Validation

Yeast engineered with toxin–antitoxin plasmids were cultured in media containing 0%,

0.1%, and 1.0%

arabinose. Viable cell counts were determined at 0, 6, 12, and 24 hours.

Figure 15. Construction and validation of toxin–antitoxin safety strain.

A.Arabinose concentration setup;

B.Experimental and control groups;

C.Plate results after incubation.

At 1.0% arabinose, colony formation was greatly reduced compared to controls,

indicating effective

arabinose-dependent safety regulation.