Public Perspective

To understand how people outside of science see antibiotic resistance and CRISPR-based solutions, we conducted a public survey that gathered over 100 responses. We wanted to know: How much do people already know about MRSA and CRISPR? What concerns do they have? And would they support a project like ours in the real world?

Awareness and Knowledge

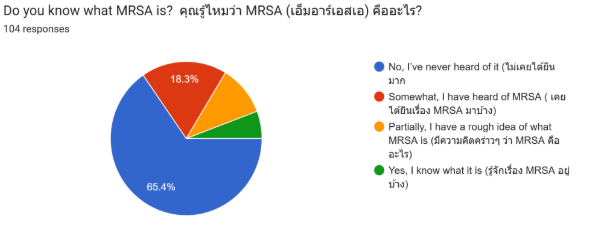

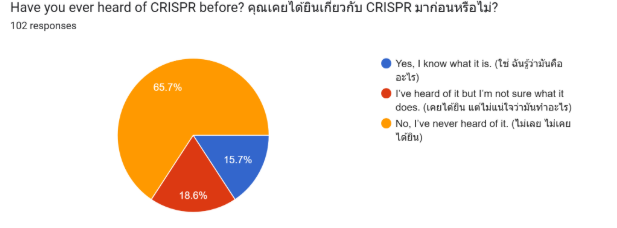

One of the clearest findings was the low awareness of MRSA (Figure 1). Around 65% of respondents had never heard of MRSA, despite it being a serious hospital-acquired infection. Similarly, a majority had never heard of CRISPR before (Figure 1).

These results showed us that education about the basics of both the problem (antibiotic resistance) and the tool (CRISPR) is essential if we want the public to understand and support new treatments.

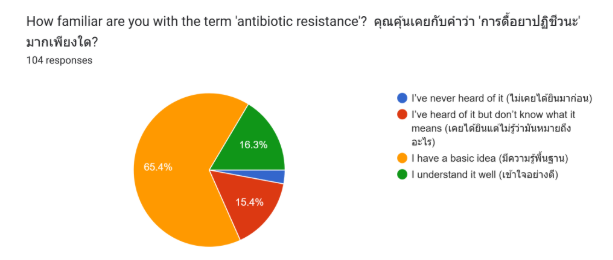

At the same time, around two-thirds of participants reported that they “knew the basics” of antibiotic resistance (Figure 2). This suggests that while people may not be familiar with MRSA specifically, they do have a general awareness that bacteria can evolve resistance to antibiotics. We saw this as an important starting point for science communication: people know the problem exists, but often not the specifics of where it is most urgent.

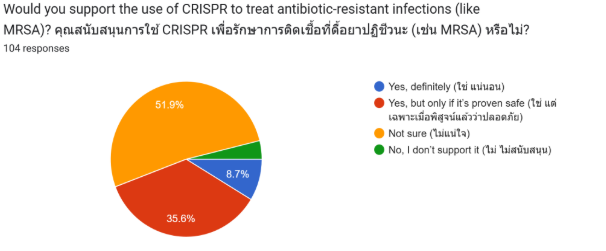

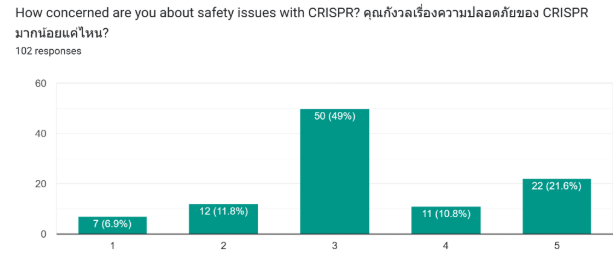

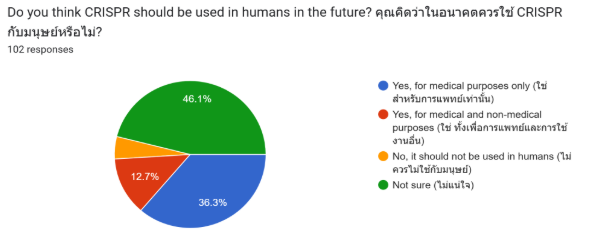

When asked how they felt about CRISPR being used in medicine, most people were cautiously supportive. About 52% were not sure, demonstrating needs for education/awareness, and 36% supported CRISPR treatments only if proven safe. Only a very small minority (4%) opposed its use outright. Safety was clearly the main concern (Figure 3). Nearly half of respondents rated their safety concerns at a “3 out of 5,” and another 22% gave it the highest level of concern. This shows that while there is excitement, there is also hesitation. People want strong evidence that CRISPR therapies are both safe and effective before they would feel comfortable with their use.

What this means for our project

The survey gave us valuable insight into how we should position our project. First, we realized that awareness and education must come first: most people don’t know about MRSA or CRISPR, so outreach is just as important as lab work. Second, we saw that safety is the deciding factor for public acceptance. Even if the science works, people won’t accept it unless they are confident it is safe.

This directly influenced how we framed our project: we decided to emphasize both biosafety measures and transparency in communication. It also guided our outreach activities, where we focused on breaking down what antibiotic resistance is, what CRISPR is, and why combining the two might help patients in the future.

Professional Perspective

To understand how synthetic biology might fit into education, we spoke with three teachers:

- Mrs. Kate Nicholls, Science Department, Saint Joseph’s Institute International Malaysia (SJIIM)

- Mr. Stuart Fyfe, Head of Science, King Mongkut’s International Demonstration School (KMIDS, Thailand)

- An anonymous teacher from Thailand, with experience teaching IGCSE, A-Level, and IB curricula

These educators gave us insight into how students currently encounter biotechnology and genetics, what challenges schools face in teaching emerging fields, and how synthetic biology could be introduced in accessible and meaningful ways.

Bridging the Curriculum Gap

All three teachers agreed that international science curricula provide a solid foundation in genetics and biotechnology but tend to lag behind scientific advances. Synthetic biology is rarely included, leaving students unaware of how the field is shaping medicine, food security, or climate solutions. As Mr. Fyfe explained, curricula updates can take years, meaning students often study content that is already behind the times.

This gap reinforced the need for outreach projects like ours to act as a bridge, helping students encounter synthetic biology earlier than the curriculum allows.

Making Synthetic Biology Accessible

Another theme was accessibility. Mrs. Nicholls noted that synthetic biology could be taught at the secondary level, but only if presented in ways that feel approachable:

“It has to be introduced in a way that is engaging and interesting for the students.”

Teachers emphasized the importance of scaffolding, starting with DNA, mutations, and proteins, before moving into applications like CRISPR or biofuels. They suggested tools such as virtual labs, simulations, inquiry-based projects, and classroom debates as effective methods, especially in schools without advanced laboratory facilities.

Relevance to Students' Lives

The teachers also highlighted the importance of connecting synthetic biology to issues students care about. For example, the anonymous Thai teacher explained that synthetic biology could be integrated with topics like sustainability or health to make lessons more meaningful. When linked to real-world challenges such as pandemics, antibiotic resistance, or food production, students are more likely to engage. This echoed our survey findings: while the public had heard of antibiotic resistance, they rarely connected it to urgent threats like MRSA. By framing CRISPR as a tool with real-world applications, educators saw opportunities to make science both exciting and relevant.

Ethics and Responsibility

Beyond content, teachers stressed that synthetic biology should always be taught alongside ethics. Mrs. Nicholls pointed out that the subject “requires critical thinking and discussion” because of its societal implications. Students should not only learn what scientists can do, but also reflect on what they should do.

This perspective aligned with our outreach goals. For our project, safety, responsibility, and public trust are not add-ons but central to how we communicate CRISPR and MRSA research.

Building Future Scientists

All three teachers expressed optimism about the potential of projects like ours to inspire the next generation. As Mr. Fyfe noted, the emphasis at the high school level should be on building transferable scientific skills like designing experiments, interpreting data, and thinking critically rather than expecting mastery of advanced techniques. Even in resource-limited settings, teachers saw opportunities: virtual labs, interdisciplinary projects, and student-led research can help students imagine themselves as scientists working on real-world problems.

What this means for our project

From these professional insights, we learned that inclusivity in science education goes beyond physical accessibility, it also means conceptual accessibility. To engage students, synthetic biology must be:

- Simplified into core concepts taught through interactive, engaging methods.

- Linked to real-world challenges like superbugs, climate change, and pandemics.

- Ethical with discussions that encourage critical thinking.

- Interesting and spark curiosity to build scientific habits of mind rather than mastery of technical details.

These perspectives shaped how we designed our Human Practices work. Our project became not just about developing a medical solution for MRSA, but also about serving as a platform for education, accessibility, and inspiration, connecting the next generation of students to the science of their future.