Inclusivity

Over 240 million children worldwide live with disabilities, yet many are denied equitable access to science education (UNICEF, 2025). 80% of STEM learning relies on visual materials, putting students with visual impairments at a significant disadvantage (Kumar & Mane, 2022). Similarly, students who are deaf or hard-of-hearing are three times less likely to pursue STEM careers due to communication barriers and inaccessible resources (Braun et al., 2018).

What We Discovered

Visual and Auditory Impairment Barriers to Participation in Science

Introduction

Science education is vital for logical thinking, informed decision-making, and societal progress (Kumar & Mane, 2022). Including students with disabilities improves diversity in problem-solving and research quality (Borger, 2024; Braun et al., 2018). Despite efforts toward inclusive education, students with visual or auditory impairments remain underrepresented in STEM fields due to inaccessible curricula, limited resources, and societal attitudes (Burgstahler & Ladner, 1994; Hayes & Proulx, 2024). These barriers stem from the learning environment rather than students’ intellectual abilities.

Visual Impairment Barriers

Visual impairment (VI) poses a major challenge in science education, as about 80% of learning relies on sight (Kumar & Mane, 2022). Science and math heavily depend on visual materials such as diagrams, graphs, and lab experiments, making abstract concepts like cell structures or planetary systems difficult to grasp without adaptations (Hayes & Proulx, 2024). Students often have limited access to Braille/audio textbooks, screen readers, and other technologies, which can delay learning and reduce participation (Battle For Blindness Foundation, 2025). In addition, many educators lack training in inclusive teaching methods, leading to lower expectations and negative attitudes that undermine students’ confidence (Battle For Blindness Foundation, 2025; Hayes & Proulx, 2024). Social and psychological challenges can arise when students cannot fully participate in classroom activities, while socioeconomic factors such as rural residence or gender compound these barriers (Chandra et al., 2025).

Current solutions focus on technology and inclusive pedagogy. Assistive tools and multisensory teaching strategies, such as tactile models, 3D graphics, and sonification of data, allow students to engage through touch or sound rather than sight (Battle For Blindness Foundation, 2025; Kumar & Mane, 2022). Future efforts should prioritize teacher training, research on accessible methods, and systemic cultural changes that value inclusion, empowering VI students to become independent learners and active contributors to science (Hayes & Proulx, 2024; Battle For Blindness Foundation, 2025).

Auditory Impairment Barriers

Students who are deaf or hard-of-hearing (DHH) face unique challenges in STEM education, affecting both communication and participation. Learning scientific content is difficult when spoken language is inaccessible, and accommodations may introduce delays or errors, especially with technical vocabulary (Braun et al., 2018). Deaf students also miss out on incidental learning, such as informal lab discussions or networking opportunities, and poor classroom arrangements can obstruct sightlines to instructors, interpreters, or visual materials. Misconceptions and stereotypes from hearing peers and faculty, such as underestimating intellectual ability or assuming hearing aids fully resolve communication challenges, further hinder participation and create unwelcoming environments (Braun et al., 2018).

Solutions for DHH students emphasize both accommodations and inclusive teaching practices. Certified interpreters, real-time captioning, preferential seating, and visual lab cues improve access to content (Braun et al., 2018; Borger, 2024). Future work should focus on reducing stereotypes and biases, increasing research on effective STEM teaching for DHH students, and developing technologies such as tracked captioning to ease cognitive load and improve accessibility (Braun et al., 2018).

Conclusion

Creating an inclusive STEM environment benefits both students and the scientific community. Technological tools, multisensory teaching, mentorship, and supportive programs empower students with visual or auditory impairments to succeed (Braun et al., 2018; Burgstahler, 1994; Hayes & Proulx, 2024). Long-term progress, however, depends on systemic changes in teacher training, institutional policies, and societal attitudes to dismantle barriers and cultivate genuine inclusion (Battle For Blindness Foundation, 2025; Borger, 2024). By continuing research, implementing accessible strategies, and advocating for equity, all students can explore science, reach their potential, and contribute meaningfully to STEM fields.

Our Inclusivity Pathways

Blind & Low-Vision Accessibility (VI)

Our commitment to making science tangible, tactile, and independent of sight.

Deaf & Hard-of-Hearing Accessibility (DHH)

Our focus on ensuring clear communication, representation, and equity in lab and classroom environments.

Our Work

Blind & Low-Vision Accessibility (VI)

Our commitment to making science tangible, tactile, and independent of sight.

Our team is committed to making science tangible, tactile, and independent of sight. To support students with visual impairments, we created Braille-based educational texts covering topics such as antibiotic resistance, MRSA, and CRISPR DNA editing. These resources allow learners to access scientific concepts in a format that is both independent and empowering. In addition, we developed interactive games and tactile activities, such as building clay models of bacterial cell walls or simulating DNA cutting with hands-on materials. These multisensory approaches help transform abstract biological processes into concrete experiences, ensuring that science is not limited to visual learners.

Deaf & Hard-of-Hearing Accessibility

Our focus on ensuring clear communication, representation, and equity in lab and classroom environments.

For students who are deaf or hard-of-hearing, our focus is on ensuring clear communication, representation, and equity in both the classroom and laboratory environments. We designed interactive educational games that emphasize collaboration and hands-on learning, including clay bacterial cell wall construction, DNA model building, and DNA cutting simulations. These activities minimize reliance on auditory explanations and instead promote understanding through tactile and visual engagement. Additionally, we adapted our educational video into a version that includes sign language interpretation alongside the visuals, ensuring that DHH students can fully access the material. This adaptation highlights our belief that accessibility must be built into scientific communication from the start, not added as an afterthought.

Stakeholder Surveys

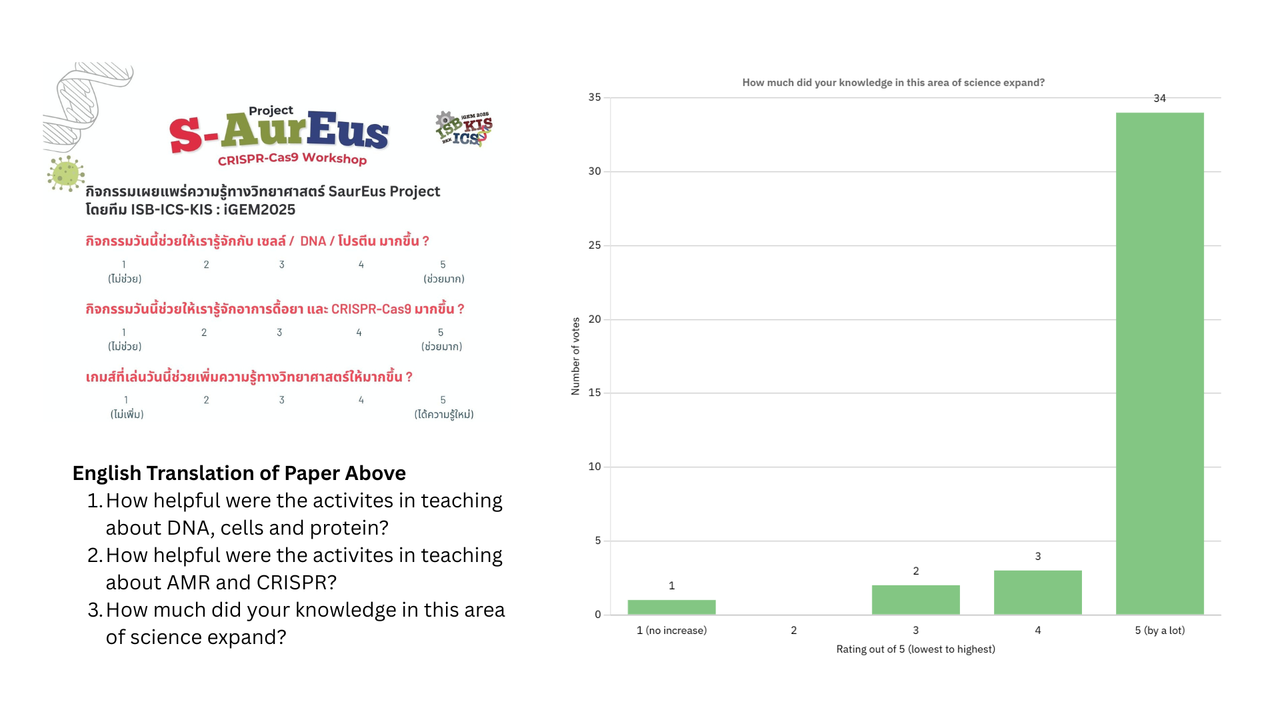

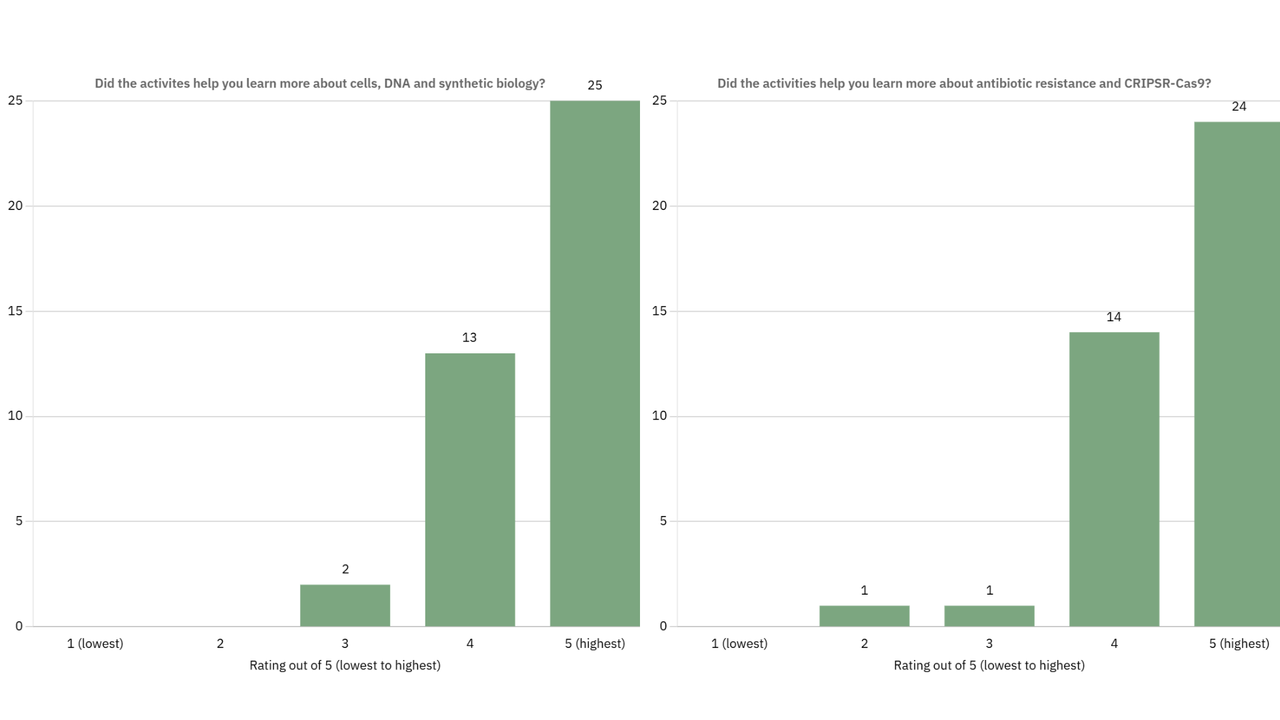

Additionally, to measure the impact of our outreach, we surveyed students at the Nakhon Pathom School for the Deaf, where we ran our synthetic biology workshop. Students were asked three questions:

- How helpful were the activities in teaching about cells, DNA, and proteins?

- How helpful were the activities in teaching about antibiotic resistance and CRISPR-Cas9?

- How much did your knowledge in this area of science expand?

The results were overwhelmingly positive.

- 84% of students rated their knowledge expansion as 5/5, saying they learned “a lot” from the session.

- Over 90% rated the activities as highly effective (4 or 5 out of 5) for learning about cells, DNA, and synthetic biology.

- Similarly, over 90% found the activities very helpful for understanding antibiotic resistance and CRISPR.

These results demonstrate that, with the right adaptations like visual aids, interactive activities, and accessible explanations, complex concepts like CRISPR can be made engaging and understandable for deaf and hard-of-hearing students. This feedback reinforced our belief that inclusivity in science education is not only possible but highly impactful. By designing workshops with accessibility in mind, we enabled students who are often excluded from STEM outreach to meaningfully engage with cutting-edge science.

Outcomes and Lessons Learned

From this process, we learned that inclusivity is not a checklist but a philosophy that must be integrated into every aspect of scientific education and outreach.

- Systemic integration is key

- True inclusion cannot be achieved by adding accommodations after the fact. Accessibility must be embedded in curriculum design, lab planning, and science communication from the very beginning.

-

Small changes have big impact

- Simple steps like adding captions to videos, incorporating tactile models, or arranging classrooms to improve visibility for interpreters can dramatically increase participation without requiring major infrastructure changes.

-

Partnership is essential

- Collaborating with disability communities ensures that solutions are co-created and grounded in lived experience, rather than imposed externally. This collaboration also builds trust and ensures that interventions meet real needs.

-

Inclusivity strengthens iGEM.

- Beyond ethics, inclusivity expands the reach and relevance of our project. By ensuring that our work is accessible to as many people as possible, we amplify the scientific and societal impact of synthetic biology.

Work for the Future

Google Drive with free-to-use printable resources and activities that we made