Model

Overview

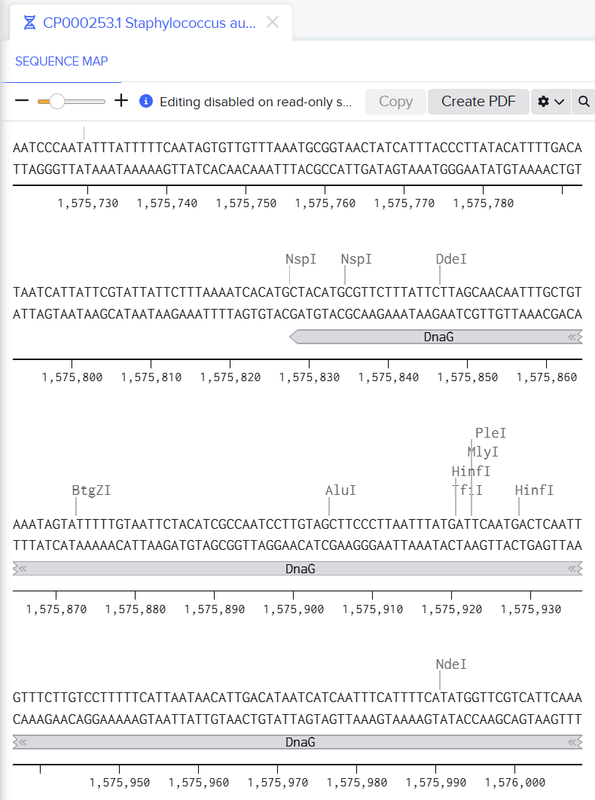

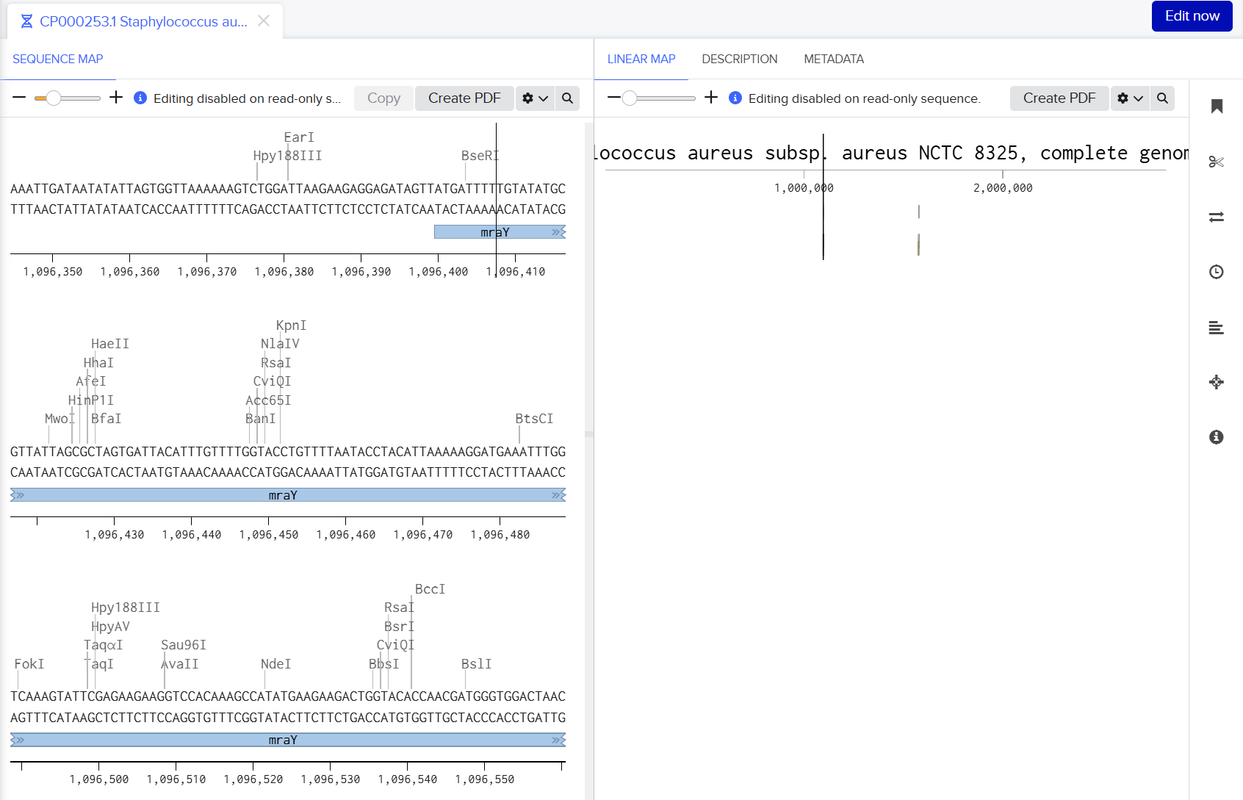

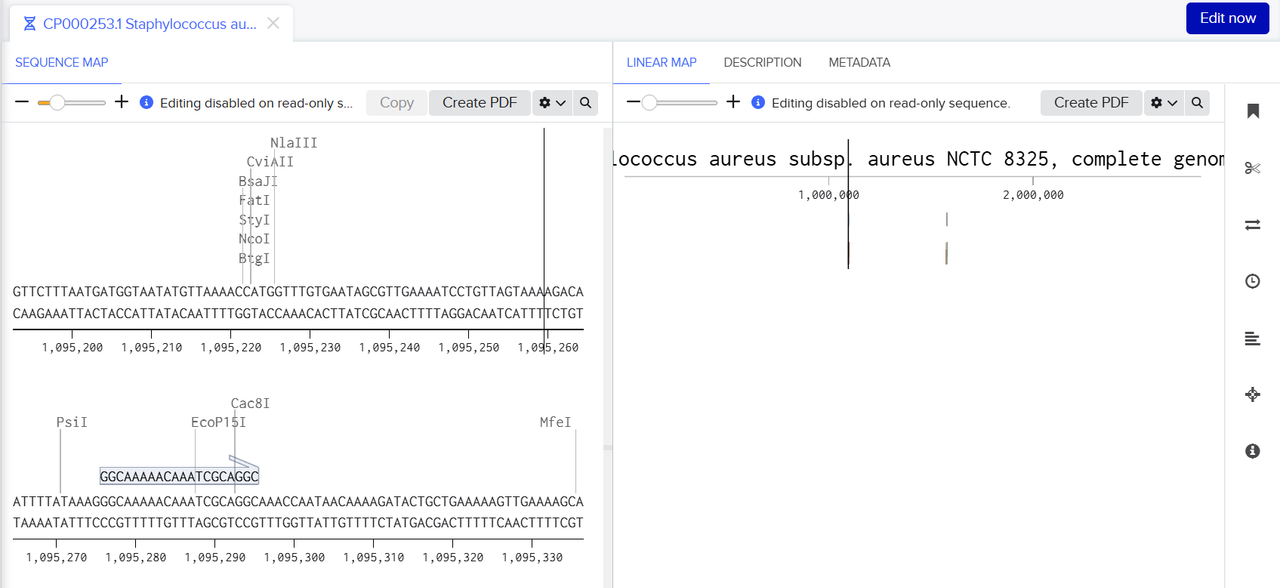

Our dry lab focused on designing and modeling the gRNAs used in CRISPR-Cas systems, and the primers used to amplify our target DNA sequences. To avoid reliance on trial-and-error in the wet lab, we focused on using computational tools to predict the efficiency of certain gRNAs and primers. We utilized CRISPR gRNA design tools such as synthego and Benchling to plan out our DNA cuts to cut our target genes, dnaG and mraY. Furthermore, we utilized Benchling, Primer3, to identify primer candidates suited for amplifying our target DNA sequences, to check for off-target activity, and to monitor the strength of primer-primer and hairpin interactions through calculating the change in enthalpy of interactions that helped us determine which primers would be suitable for our project. Combining predictions with modeling, we aimed to select gRNAs and primers that maximized on-target efficiency and minimized any off-target risks, and were able to generate a short list of the most promising gRNAs and primers, which guided the wet lab team’s experiments. This approach allowed for a more efficient and streamlined project, saving time and resources while also increasing the likelihood of success in the wet lab.

Background

CRISPR-Cas systems are useful tools for genome editing that allow scientists to cut DNA at specific and precise locations. At the heart of this process is the guide RNA (gRNA), a short sequence of RNA that directs the Cas protein (Cas9) to the correct target site in the genome. The gRNA then binds to the target DNA through base pairing, and the Cas protein then carries out the cut at the specific site.

The gRNA must be designed effectively for CRISPR to work properly and accurately. If the gRNA sequence is well-matched to the target DNA, the editing will be more efficient and accurate; this is also known as high on-target efficiency. However, if the gRNA also matches similar regions in the genome, the Cas protein may cut sites that were not the intended target (off-target effects), which can lead to harmful mutations or unpredictable outcomes after the gene is edited.

PCR primers are short synthetic single-stranded DNA segments that are used to amplify specific parts of an organism’s genome or DNA samples through Polymerase Chain Reaction, or PCR. The process of polymerase chain reaction works through the use of DNA polymerase, template, DNA, forward and reverse PCR primers, and a thermal cycle that allows for exponential replication of DNA fragments using DNA polymerase which is guided to the correct starting point of DNA replication through PCR primers, doubling the target DNA in each thermal cycle. Like gRNAs, PCR primers must also be designed to match target DNA well, and be highly specific to target DNA sequences to decrease off-target effects, however the effects of off-target PCR primers lead to unintended DNA sequences being amplified along with target DNA sequences instead of causing harmful mutations or unpredictable outcomes like the off-target effects of gRNAs.

Because of this, gRNA and PCR primer design is not just a wet lab task; it also greatly benefits from analysis using digital tools. In the dry lab, we can use bioinformatics tools like BLAST to predict which gRNAs and PR primers are most likely to succeed and which may cause problems. By modeling and simulating the behavior of the gRNA or PCR primer before we carry out experiments, we improve both the reliability and efficiency of this project.

Method

To design and evaluate gRNAs, we used a combination of bioinformatics and modeling tools. gRNAs were generated with platforms such as CHOPCHOP and Benchling, which provided scores for how efficient each gRNA was, along with the potential for off-target binding. To further validate our gRNA targets and ensure specificity, we employed the BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) algorithm. BLAST was used to compare our gRNA target sequences against reference genomes and protein databases to identify any regions of unintended similarity. The process involved submitting each gRNA sequence as a query, which BLAST then compared to a comprehensive sequence database. The algorithm first identified short exact matches (seeds) and extended them to find longer local alignments, allowing for mismatches and gaps. Each alignment was given a similarity score and an E-value, with lower E-values indicating a lower probability of a match occurring by chance.

The resulting alignments enabled us to confirm whether the designed gRNAs were highly specific to the intended genomic locus and to avoid those with significant off-target hits. This step ensured that the final set of gRNAs selected for downstream experiments had high predicted efficiency while minimizing the risk of off-target gene editing.

To design and evaluate PCR primers, we utilized Primer3 to generate suitable PCR primers for 2 DNA sequences that contained either mraY or dnaG surrounded by a couple kbp of surrounding DNA that would act as CRISPR-cas9 target sites. This was done through feeding the DNA sequences into Primer3, which would generate a ranked list of PCR primer primers by order of suitability. We would then use benchling to run BLAST and check if the primers appeared in other locations in the S. aureus genome to determine the off-target effects of each PCR primer, which allowed us to create a list of possible PCR primer pairs that we could use to amplify each DNA sequence in our lab.

Conclusion

Overall, our dry lab analysis of gRNA and PCR primer design provided essential information as well as acted as a guideline for the more experimental side of the project. By combining the use of bioinformatics tools, predictive modeling, and structural analysis, we identified which gRNAs and PCR primers were expected to have high efficiency and low risk of off-target effects. This reduced the need for random trial-and-error in the wet lab and allowed us to save time and resources during experiments. Beyond saving time and resources, the modeling also gave us a deeper understanding of how gRNA and PCR primer structure, sequence selection, and off-target potential influence CRISPR as a tool. To conclude, the integration of dry and wet lab efforts strengthened our project by ensuring that experimental work was informed by predictions, embodying a disciplined and efficient approach to genetic editing.