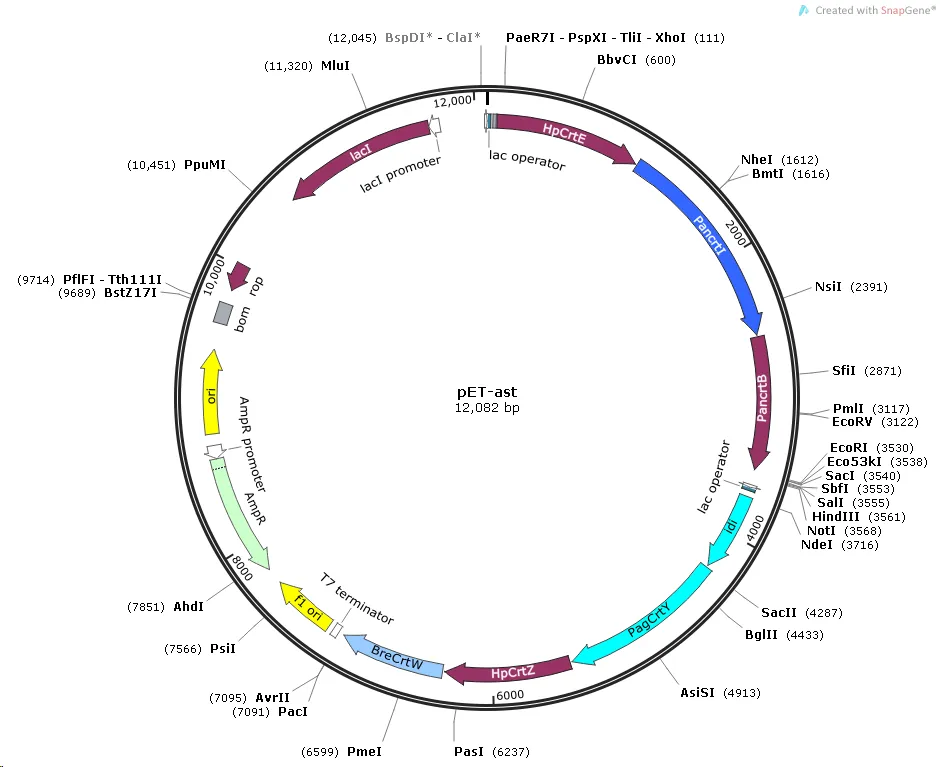

Astaxanthin is a potent antioxidant with anti-aging effects, widely demanded by cosmetics and skincare manufacturers in society. However, the current low yield of astaxanthin leads to its high price [1] . NSFLS China 2025 is committed to using genetically modified E.coli to produce astaxanthin, replacing the traditional production method using Haematococcus pluvialis. The E.coli is engineered with a specially designed pET-Duet-1 plasmid, enabling the production of large amounts of astaxanthin through IPTG-induced expression (Figure 1). Our product features mature technology, low cost, and environmental friendliness. We hope to meet the market's demand for more high-quality astaxanthin through this approach.

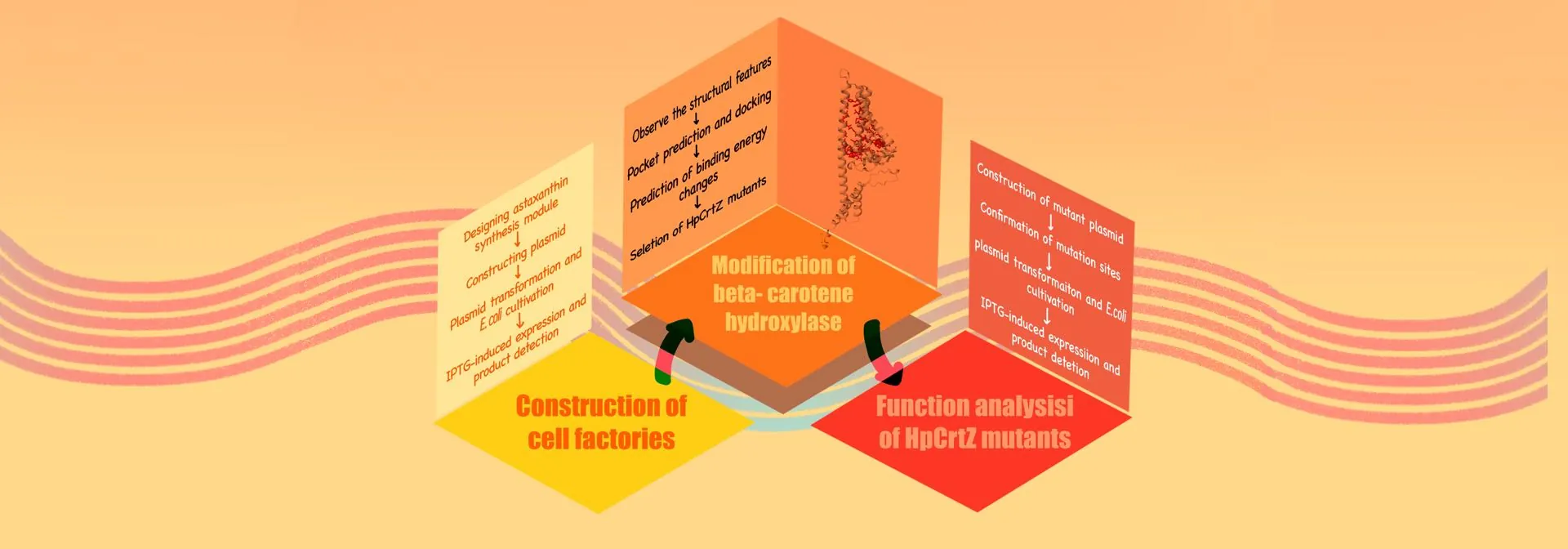

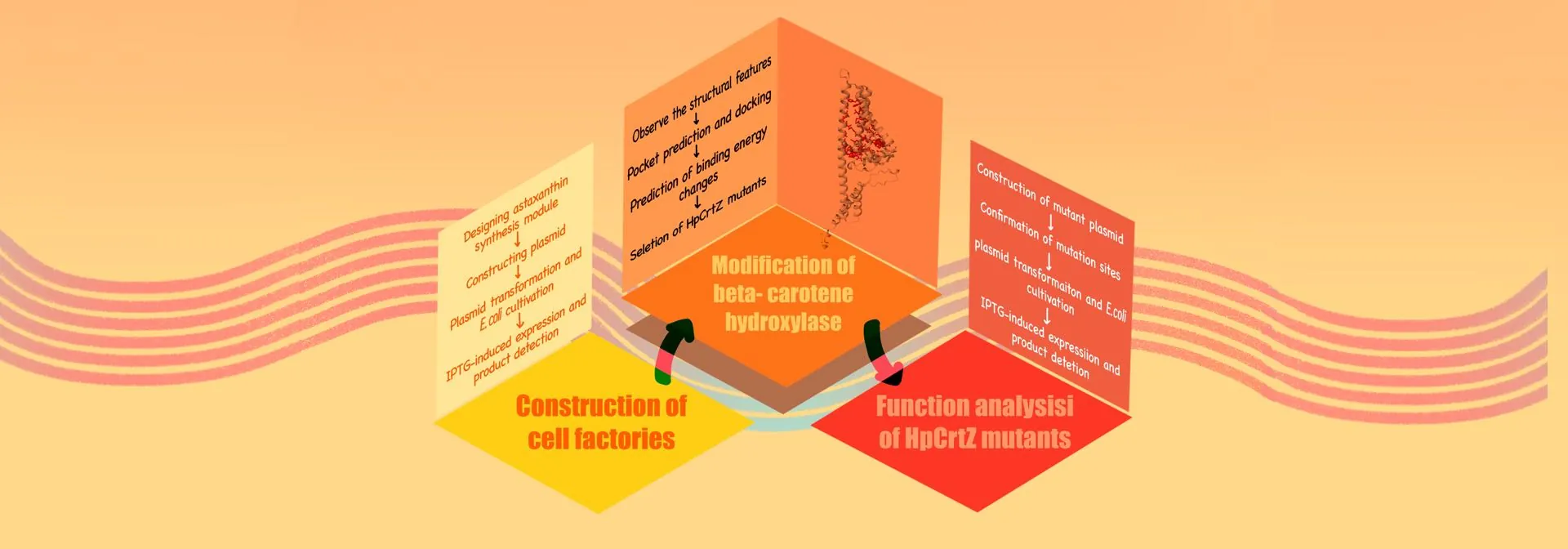

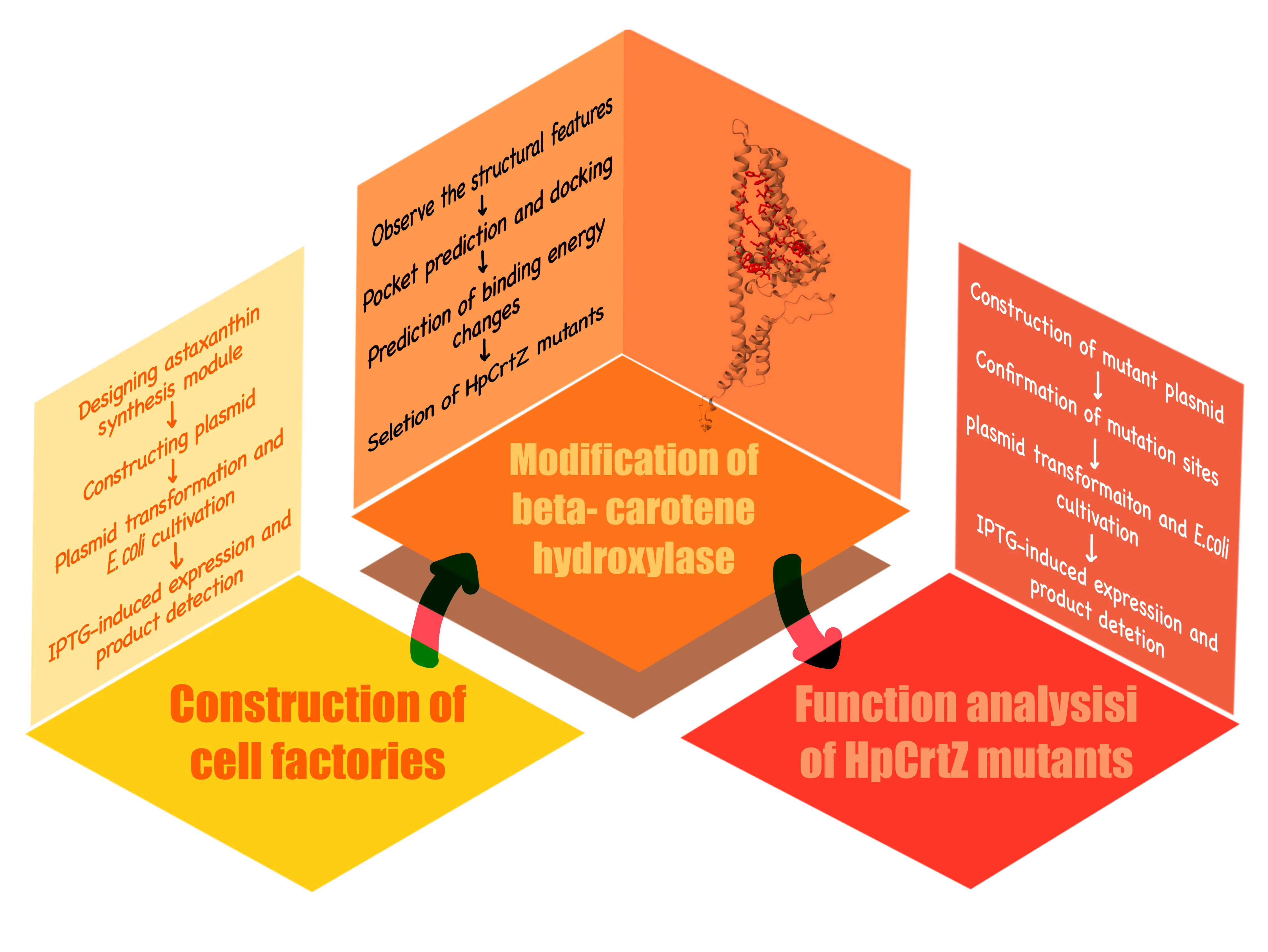

Figure 1.The flowchart of our research process

Figure 1.The flowchart of our research process

Regarding the design of the astaxanthin synthesis module, we consulted a paper from Wuhan University [2]. Their experiment, combining PacBio and Illumina sequencing technologies, completed the whole genome sequencing of Sphingomonas sp. ATCC 55669, identified key genes in the astaxanthin biosynthetic pathway (such as crtE, crtB, crtI, crtY, crtZ, crtW, idi), optimized them, and confirmed the feasibility of producing astaxanthin using these genes. Through the experiments from Wuhan University, it was found that the astaxanthin synthesis pathway in pFZ153 far exceeded other pathways. Therefore, we selected pFZ153 as the basic plasmid for our synthesis module. Our designed synthesis pathway includes the following key enzyme genes including idi, CrtE, CrtB, CrtI, CrtY, CrtZ, CrtW(Figure 2).

Figure 2.Astaxanthin Biosynthesis Pathway

Figure 2.Astaxanthin Biosynthesis Pathway

These genes together constitute the complete synthesis pathway from IPP/DMAPP to astaxanthin: IPP/DMAPP → Lycopene → β-Carotene → Canthaxanthin → Astaxanthin

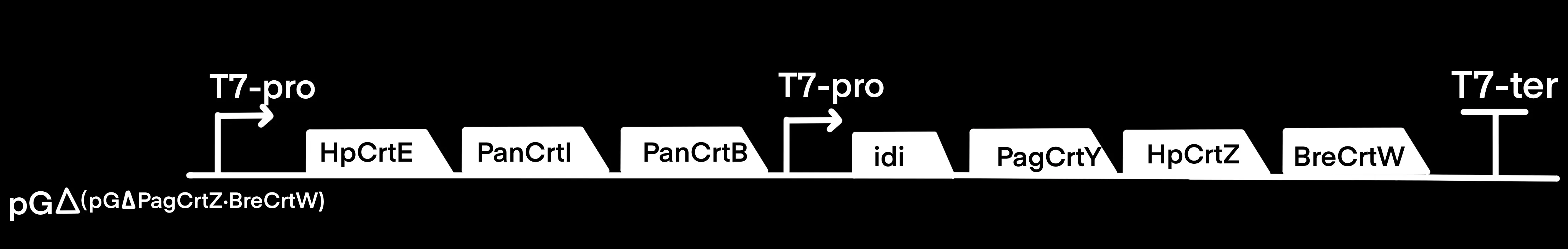

Haematococcus pluvialis is currently the main natural source of astaxanthin, and its astaxanthin content can reach up to 10% of its dry weight. To enhance astaxanthin biosynthesis, we utilized HpCrtE from Haematococcus pluvialisand replaced the original CrtE gene in the pFZ153(Figure 3) pathway [3]. HpCrtZ is derived from Haematococcus pluvialis which possess higher catalytic activity [4]. Then HpCrtZ replaced the original CrtZ gene in the pFZ153(Figure 3) pathway [5].

Figure 3.Construction of pET-ast plasmid

Figure 3.Construction of pET-ast plasmid

We selected pET-Duet-1 as the expression vector. This vector contains two independent T7 promoters, supporting the co-expression of multiple genes. Each promoter can accommodate 3-4 genes, facilitating modular expression. It is suitable for the E.coli BL21(DE3) expression system and offers high induction expression efficiency.

The host strain E.coli BL21(DE3) is chosen. It is deficient in proteases, reducing target protein degradation. It is compatible with the T7 expression system, allowing for high-efficiency IPTG-induced expression. It grows rapidly, is easy to culture, suitable for large-scale fermentation, and conducive to future industrial application.

We used AlphaFold 2 to predict the three-dimensional structure of β-carotene hydroxylase and PrankWeb to identify its substrate-binding pocket. This pocket is formed by multiple transmembrane helices, creating a hydrophobic channel that is crucial for substrate binding and catalysis. Identifying the pocket structure helps understand the enzyme's mechanism of action and provides a structural basis for subsequent rational design.

Molecular docking simulations (using CB-Dock2) were performed to analyze the binding energy between the wild-type/alanine mutants and the substrates (canthaxanthin, β-carotene). A lower binding energy indicates a more stable substrate-enzyme complex and potentially higher catalytic efficiency. We screened several mutation sites with significantly reduced binding energy, including ILE102, SER96, CYS191, THR213, etc., as potential high-efficiency mutant candidates (Figure 4).

Figure 4.Experimental Flow Chart

Figure 4.Experimental Flow Chart

To validate the function of the mutants, we constructed HpCrtZ alanine mutant plasmids via chemical synthesis (synthesized by GenScript), then transformed these mutant plasmids into E.coli BL21(DE3) to obtain engineered strains. After inducing expression with IPTG, bacterial cells were collected and carotenoids were extracted.

We employed high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) for quantitative analysis of astaxanthin yield, comparing the production capabilities between the mutants and the wild-type.

The results showed that the astaxanthin yield of some mutants (such as CYS191ALA,ILE102ALA) was significantly higher than that of the wild-type, validating the effectiveness of the rational design.

[1]Higuera-Ciapara I., Félix-Valenzuela L., Goycoolea F. M. Astaxanthin: a review of its chemistry and applications. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 2006, 46(2):185-196.

[2] Wang W, Li Y, Hu Z, et al. Genome mining of astaxanthin biosynthetic genes from Sphingomonas sp. ATCC 55669 for heterologous overproduction in E. coli. Biotechnol J. 2016;11:228–237.

[3] Huang D, Liu W, Li A, Wang C, Hu Z. Discovery of geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate synthase (GGPPS) paralogs from Haematococcus pluvialis based on Iso-Seq analysis and their function on astaxanthin biosynthesis. Mar Drugs. 2019;17:696.

[4] Huang DQ, Liu WF, Li AG, Hu ZL, Wang JX, Wang CG. Cloning and identification of a novel β-carotene hydroxylase gene from Haematococcus pluvialis and its function in Escherichia coli. Algal Research.2021, 55(22):102245.

[5] Shah MMR, Liang Y, Cheng J, Daroch M. Astaxanthin-producing green microalga Haematococcus pluvialis: from single cell to high value commercial products. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:531.