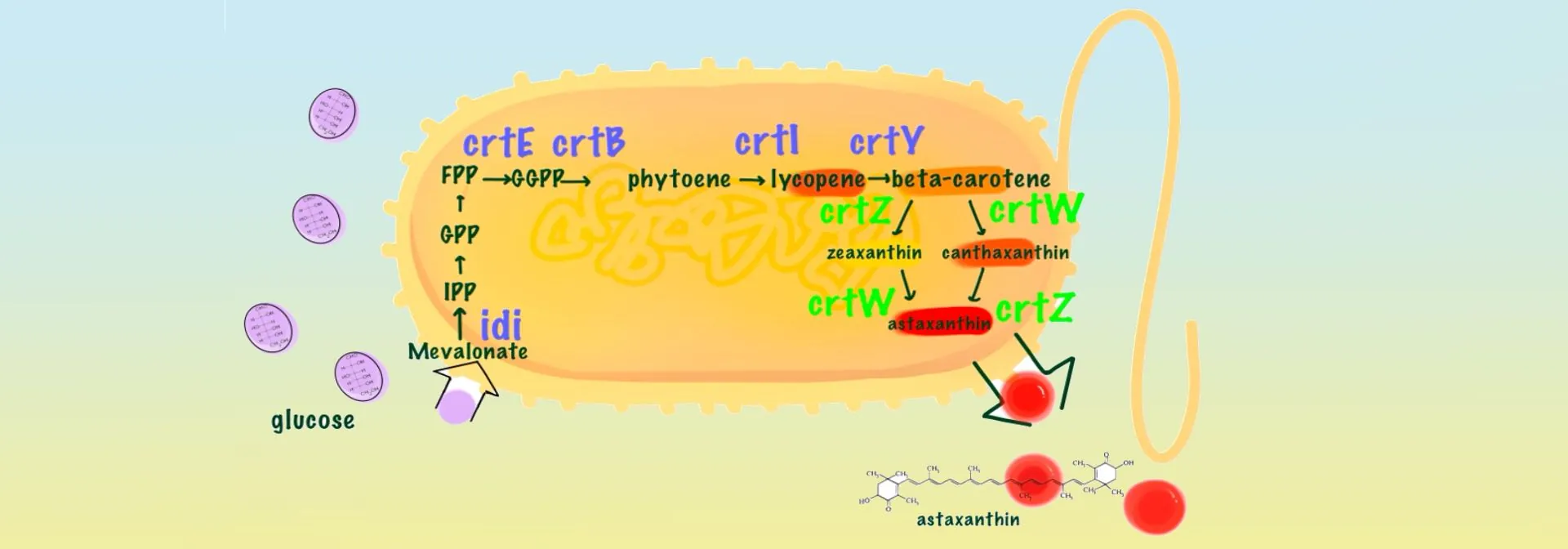

Astaxanthin is a potent antioxidant with anti-aging properties and is widely sought after by manufacturers of cosmetics and skin care products [1]. However, current production is low, resulting in high market prices [2]. NSFLS China 2025 is dedicated to the production of astaxanthin using Escherichia coli as a cellular factory as an alternative to the traditional astaxanthin obtained from Haematococcus pluvialis. For astaxanthin synthesis, IPP and DMAPP are progressively condensed to geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate (GPP) and farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP) by isopentenyltransferase, and then converted to geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate (GGPP) by the action of GGPP synthase (GGPPS/CrtE). This is followed by the production of phytoene lycopene (phytoene) catalysed by phytoene lycopene synthetase (CrtB) and the subsequent formation of lycopene by phytoene lycopene dehydrogenase (phytoene desaturase, CrtI). β-carotene is produced in the presence of lycopene β-cyclase (CrtY). β-carotene is subsequently converted into astaxanthin through the synergistic action of β-carotene hydroxylase (CrtZ) and β-carotene ketolase (CrtW) [3]. Our study planned to optimise the astaxanthin synthesis pathway by expressing seven genes (crtE, crtB, crtI, crtY, crtZ, crtW and idi, respectively) necessary for the synthesis of astaxanthin in E. coli using the two T7 promoters of the pET-Duet-1 vector. In addition, we targeted the modification of β-carotene hydroxylase, the rate-limiting enzyme for astaxanthin synthesis, using rational design. Finally, we induced the expression of the target gene by IPTG to achieve efficient astaxanthin synthesis in E. coli. Our technology is mature, cost-effective and environmentally sustainable. We aim to meet the market demand for high quality astaxanthin through this approach.

In terms of the design of astaxanthin synthesis module, a literature revealed that Liu T et al [4] mined the key genes for astaxanthin biosynthesis from the genome of Sphingomonas spp. ATCC 55669, and they identified key genes in the astaxanthin biosynthesis pathway (e.g., crtE, crtB, crtI, crtY, crtZ, crtW, and idi), the gene combinations were optimised and the potential of these genes to produce astaxanthin was confirmed. Their experiments showed that the astaxanthin synthesis module of pFZ153 plasmid includes crtE, crtI, crtB, idi, crtY, crtZ, crtW, and the gene arrangement order is crtEIB-idi-crtYZW, which is a synthesis pathway with significantly higher efficiency than other pathways. Therefore, we chose pFZ153 as the departure module for astaxanthin synthesis.

Literature shows that Huang DQ et al [5] found geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate synthase gene (HpCrtE) from Haematococcus pluvialis to improve the synthesis efficiency of astaxanthin, which is 2.7-3 times higher than that of the CrtE from bacteria. Therefore, we replaced CrtE in the pFZ153 pathway with HpCrtE from Haematococcus pluvialis. β-Carotene hydroxylase is the key enzyme that can convert canthaxanthin into astaxanthin. Haematococcus pluvialis is currently the main natural source of astaxanthin, and its astaxanthin content can reach up to 10% of dry weight, based on which we can speculate that β-carotene hydroxylase from Haematococcus pluvialis has higher catalytic activity [6], and that HpCrtZ has an advantage in the efficient synthesis of astaxanthin. We replaced CrtZ in the pFZ153 pathway with HpCrtZ from Haematococcus pluvialis. Through our optimised astaxanthin synthesis pathway, we chose the following combination of genes: HpCrtE from Haematococcus pluvialis, PanCrtB from Pantoea ananatis, PanCrtI from Pantoea ananatis, idi from E. coli, PagCrtY originating from Pantoea agglomerans, HpCrtZ from Haematococcus pluvialis , and BreCrtW originating from Brevundimonas sp. SD212 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Design of astaxanthin synthesis pathway

Figure 1. Design of astaxanthin synthesis pathway

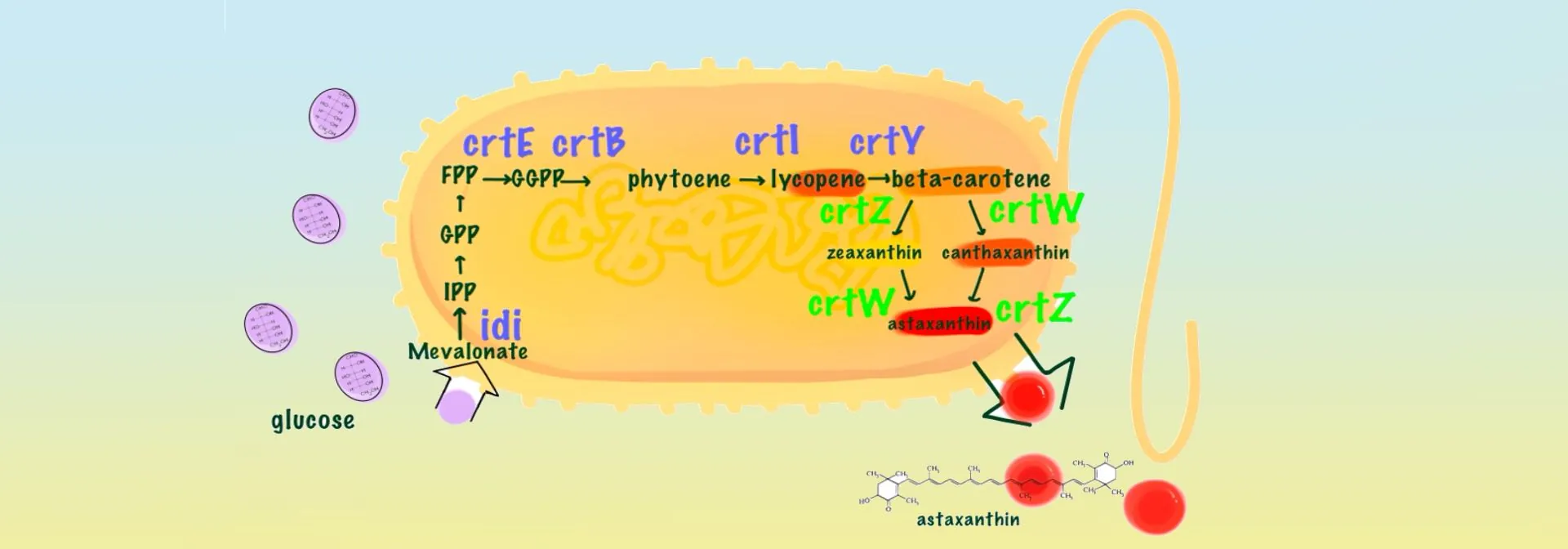

We chose pET-Duet-1 as the starting vector, using both HpCrtE-PanCrtI -PanCrtB and idi-PagCrtY-HpCrtZ-BreCrtW as an expression module. Then we entrusted GenScript Biotechnology to catalyse them,thus inserted them into the enzyme cleavage site of pET-Duet-1 respectively to obtain pET-ast plasmid (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Construction of pET-ast plasmid

Figure 2. Construction of pET-ast plasmid

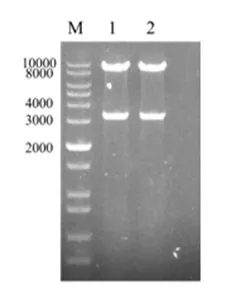

In order to confirm the success of the plasmid construction, we analysed the plasmid by restriction digestion. pET-ast plasmid was digested by two restriction enzymes, Pac I and Nde I, and two clear and correct bands were observed, which indicated that the plasmid construction was successful (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Enzymatic identification of pET-ast plasmid

Figure 3. Enzymatic identification of pET-ast plasmid

M: 1kb plus DNA ladder; 1-2: Products after Pac I/ Nde I digestion

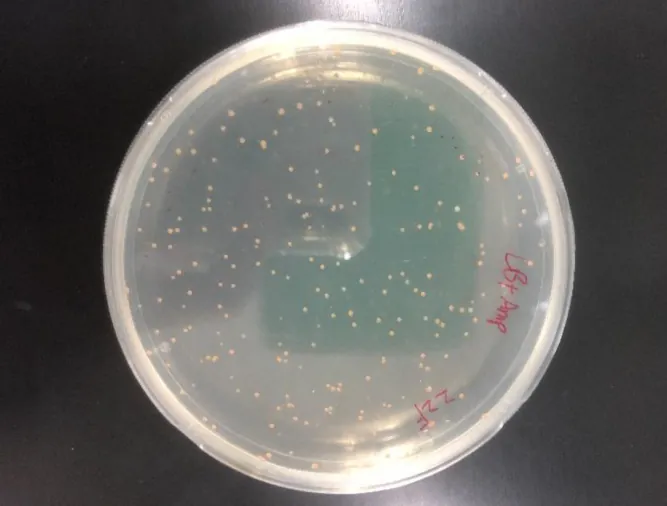

In order to overexpress the gene module for astaxanthin synthesis in E. coli, we need to transform pET-ast into E. coli BL21(DE3). Under the induction of IPTG, two gene modules, HpCrtE-PanCrtI -PanCrtB and idi-PagCrtY-HpCrtZ-BreCrtW, will be able to be efficiently expressed driven by the dual T7 promoter [7] to catalyse astaxanthin. We transferred the pET-ast plasmid into E. coli BL21(DE3) by the heat shock method and screened it on medium containing ampicillin. After overnight incubation, we obtained many monoclones (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. pET-ast transformation of E. coli BL21(DE3)

Figure 4. pET-ast transformation of E. coli BL21(DE3)

The pET-ast plasmid was transformed into E. coli BL21 (DE3) and was screened to obtain monoclonal colonies [8]. The monoclonal colonies were picked and inoculated in 3-5 mL of LB liquid medium containing ampicillin, and the test tubes were placed in a constant temperature shaker at 37°C, 220 rpm for 12-16 hours. On the following day, the cultures were inoculated into fresh LB medium and incubated until OD600=0.5-0.6 and induced by adding IPTG at a final concentration of 0.1 mM for 4-6 hours [9-11]. The culture was centrifuged and the supernatant was removed to obtain E. coli cells containing astaxanthin and a red precipitate could be seen (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Obtained E. coli containing astaxanthin

Figure 5. Obtained E. coli containing astaxanthin

The E. coli cells were vacuum freeze-dried to remove water, and methanol:isopropanol solvent was added for pigment extraction. The pigments obtained from the extraction were determined by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) to obtain the content of astaxanthin, canthaxanthin, β-carotene and other products. As shown in Figure 6, the content of β-carotene was 0.9 mg/g (DCW), canthaxanthin was 3.88 mg/g (DCW) and astaxanthin was 1.3 mg/g (DCW).

The above results indicated that the engineered pathway successfully converted a large amount of β-carotene into downstream products. However, the significant accumulation of canthaxanthin, compared to astaxanthin, suggested that β-carotene hydroxylase had relatively low efficiency in converting canthaxanthin to astaxanthin. Therefore, we considered the rational design approach to modify β-carotene hydroxylase to improve its catalytic activity.

Figure 6. Analysis of the ability of pET-ast to synthesize astaxanthin

Figure 6. Analysis of the ability of pET-ast to synthesize astaxanthin

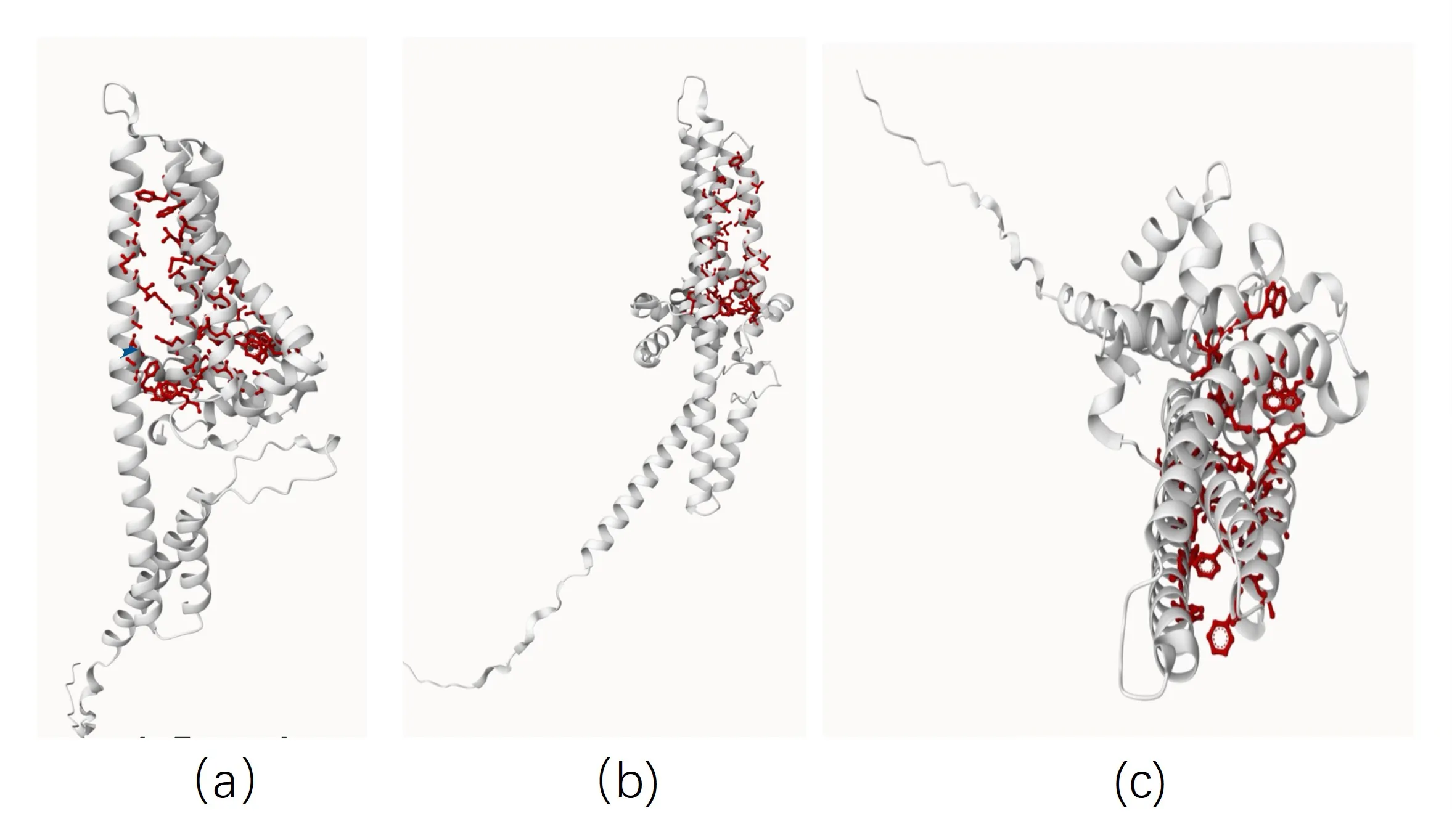

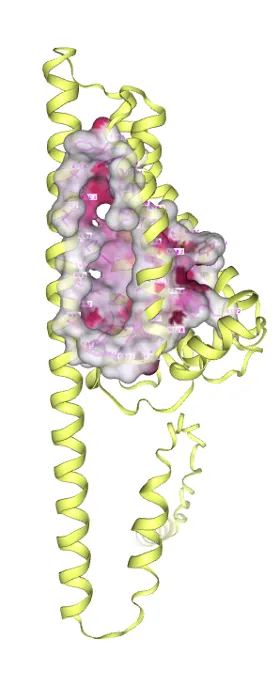

Firstly, the 3D structure of β-carotene hydroxylase (No. Q9SPK6) was obtained using alphafold2 and put into cbdock2 to open it for observation [12].

The front view (Figure 7-a) shows that the protein exhibits a highly helical structure dominated by α-helices (white coils). A distinct hydrophobic pocket (binding cavity) is formed in the centre, possibly acting as a substrate binding site. The C-terminus (carboxyl-terminus, termination end) is elongated and extends in a disordered fashion.

Lateral view (Figure 7-b) The transmembrane structure is clearly visible with at least seven transmembrane helical regions (typical GPCR-like pattern). The hydrophobic regions are symmetrically distributed, supporting their localisation embedded in the membrane.

Top view (Figure 7-c) The central channel structure formed by the α-helices is observed. The red residue side chain forms a hydrophobic channel within the pore, facilitating the entry of lipophilic molecules (e.g., carotenoid substrates.) The N-terminal (amino-terminal, initiating) region (left extended region) is an unstructured structural domain, which may have a regulatory function or be involved in localisation. β-carotene is predicted using CBdock2.

Figure 7. The 3D structure of β-carotene hydroxylase in front view (a), side view (b), and vertical view (c)

Figure 7. The 3D structure of β-carotene hydroxylase in front view (a), side view (b), and vertical view (c)

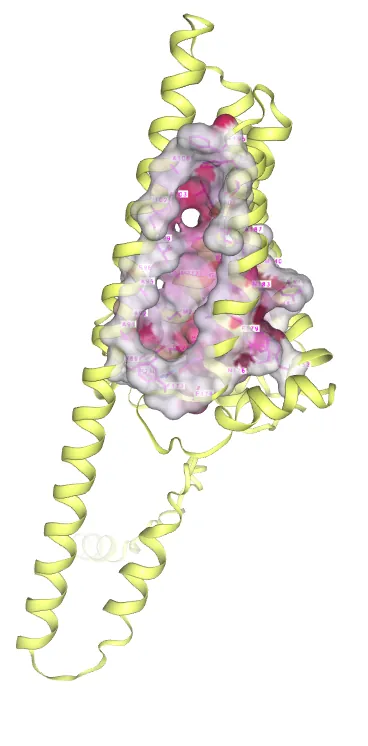

We downloaded the protein structure of β-carotene hydroxylase (Q9SPK6) in Alphafold2, obtained the structures of the substrates canthaxanthin (CID: 5281227) and β-carotene (CID: 5280489) in Pubchem, and used CB-Dock2 to predict the binding mode between β-carotene hydroxylase and its substrates, thus predicting the amino acid sites in its substrate-binding region. β-carotene hydroxylase docking to canthaxanthin showed a docking score of -6.7, and the amino acid sites involved in substrate binding included TYR88, TRP152, HIS165, GLU174, ASN176, ASP177, PHE179, ALA180, ASN183, GLY216, TYR219, MET220, HIS223, ASP224, ARG230 (see Figure 8).

Figure 8. Molecular docking of canthaxanthin with β-carotene hydroxylase

Figure 8. Molecular docking of canthaxanthin with β-carotene hydroxylase

Docking score between β-carotene hydroxylase and β-carotene is -10.6. Amino acid sites involved in substrate binding include TYR88, VAL99, ILE102, ALA103,PHE105, ALA106, LEU109, MET140, TRP152, ASN176, ASP177, PHE179, ALA180, ASN183, GLY184, ALA187, MET188, CYS191, THR192, PHE195, TRP196, LEU210, ILE212, THR213, GLY216, MET217, TYR219, MET220, HIS223, ASP224, (see Figure 9).

Figure 9. Molecular docking of β-carotene with β-carotene hydroxylase

Figure 9. Molecular docking of β-carotene with β-carotene hydroxylase

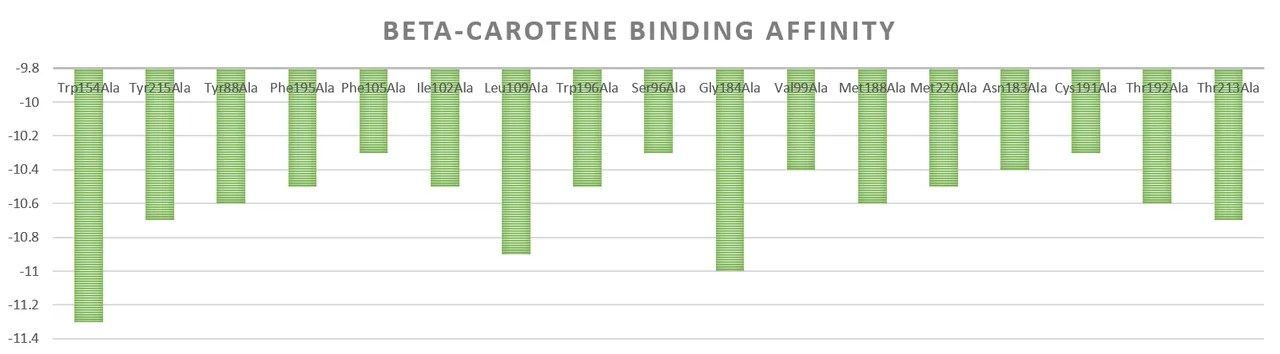

In response to the problem of canthaxanthin accumulation encountered in the previous experiments, the possible cause was the insufficient activity of β-carotene hydroxylase. Alanine is the smallest amino acid in molecular size among all amino acids, which facilitates enzyme-substrate binding and reduces enzyme-substrate binding energy through site-blocking effect [13], after each pocket region was mutated to alanine, its binding energies with astaxanthin and β-carotene were analysed separately. Fig. 10 demonstrates the changes in the binding energies of β-carotene-enhancing enzyme mutants with β-carotene, and the majority of the sites have a binding affinity below -10.

Figure 10. Change in binding energy of β-carotene with β-carotene hydroxylase mutants

Figure 10. Change in binding energy of β-carotene with β-carotene hydroxylase mutants

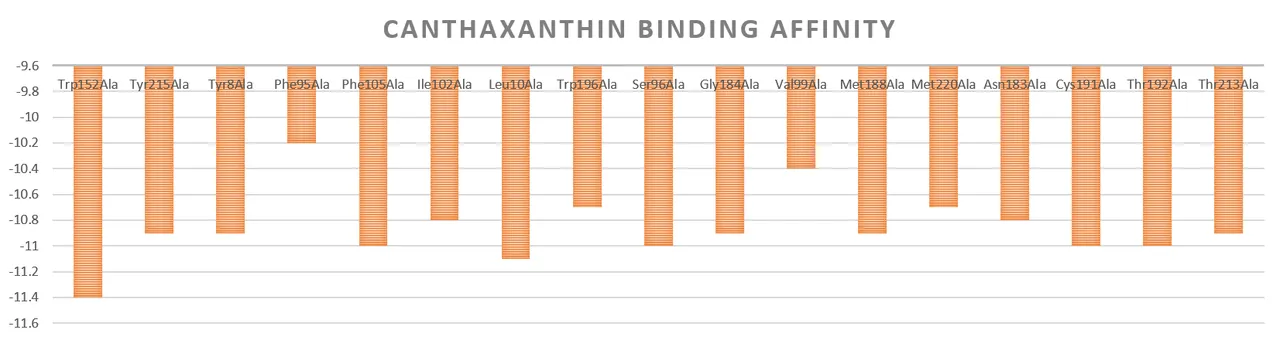

As shown in Figure 11, it demonstrates the changes in the binding energy of β-carotene hydroxylase mutants to canthaxanthin. Compared with the unmutated β-carotene hydroxylase, the binding energies of the β-carotene hydroxylase mutants ILE102ALA, SER96ALA, CYS191ALA, and THR213ALA to canthaxanthin were significantly lower than the average value, showing that they have a role in enhancing β-carotene hydroxylase activity with potential.

Figure 11. Changes in the binding energy of canthaxanthin to β-carotene hydroxylase mutants.

Figure 11. Changes in the binding energy of canthaxanthin to β-carotene hydroxylase mutants.

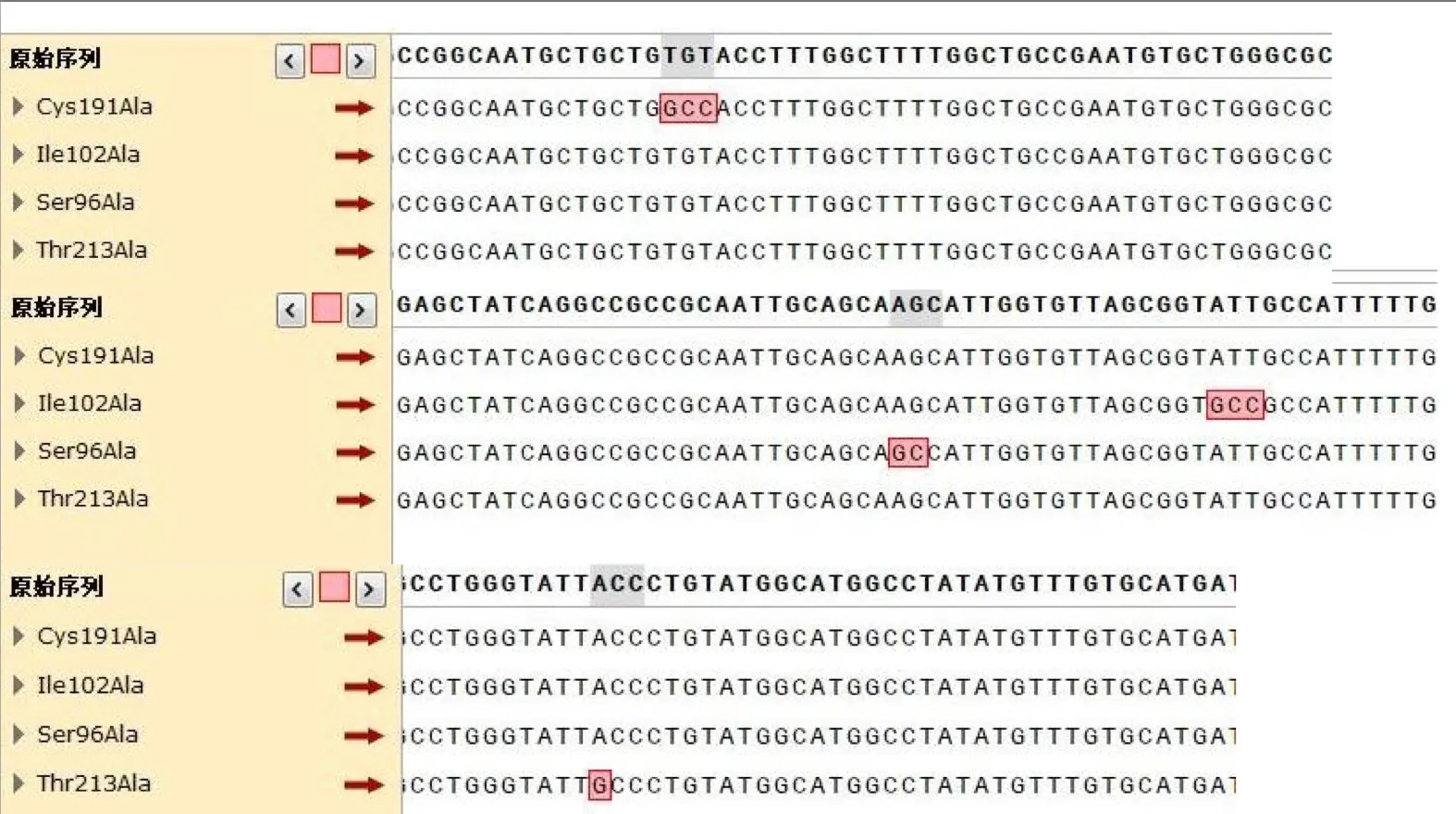

Based on the analysis of the binding energy of β-carotene hydroxylase mutants with β-carotene and canthaxanthin, the binding energy of β-carotene hydroxylase mutants ILE102ALA, SER96ALA, CYS191ALA, and THR213ALA with canthaxanthin was decreased, which promotes the binding of substrate and is conducive to the improvement of the enzyme's catalytic activity. Therefore, we selected four sites for targeted mutagenesis, namely ILE at position 102 to ALA, SER at position 96 to ALA, CYS at position 191 to ALA, and THR at position 213 to ALA.The four β-carotene hydroxylase mutants were obtained by chemical synthesis, and synthesized by GenScript Biotech (Nanjing). The catalysed plasmids were verified by sequencing and replaced HpCrtZ on pET-ast to obtain 4 mutant plasmids pET-ast (ILE102ALA), pET-ast (SER96ALA), pET-ast (CYS191ALA), pET-ast (THR213ALA) (see Figure 12).

Figure 12. Confirmation of mutation sites by sequencing. Cysteine 191 (TGT) mutated to alanine (GCC), isoleucine (ATT) at position 102 mutated to alanine (GCC), serine 96 (AGC) mutated to alanine (GCC), threonine (ACC) at position 213 mutated to alanine (GCC)

Figure 12. Confirmation of mutation sites by sequencing. Cysteine 191 (TGT) mutated to alanine (GCC), isoleucine (ATT) at position 102 mutated to alanine (GCC), serine 96 (AGC) mutated to alanine (GCC), threonine (ACC) at position 213 mutated to alanine (GCC)

The mutant plasmids pET-ast (ILE102ALA), pET-ast (SER96ALA), pET-ast (CYS191ALA), and pET-ast (THR213ALA) were transformed into E. coli BL21 (DE3) by heat-shock method, and monoclonal colonies were obtained by screening. The monoclonal colonies were picked and cultured overnight.

On the next day, the cultures were inoculated into fresh LB medium and cultured until OD600=0.5-0.6 . Then, IPTG at a final concentration of 0.1 mM was added for induction for 5 hours. Cultures were centrifuged, depleted, vacuum freeze-dried to obtain lyophilised bacterial powder, and methanol:isopropanol solvent was added for pigment extraction. The pigments obtained by extraction were determined by high performance liquid chromatography.

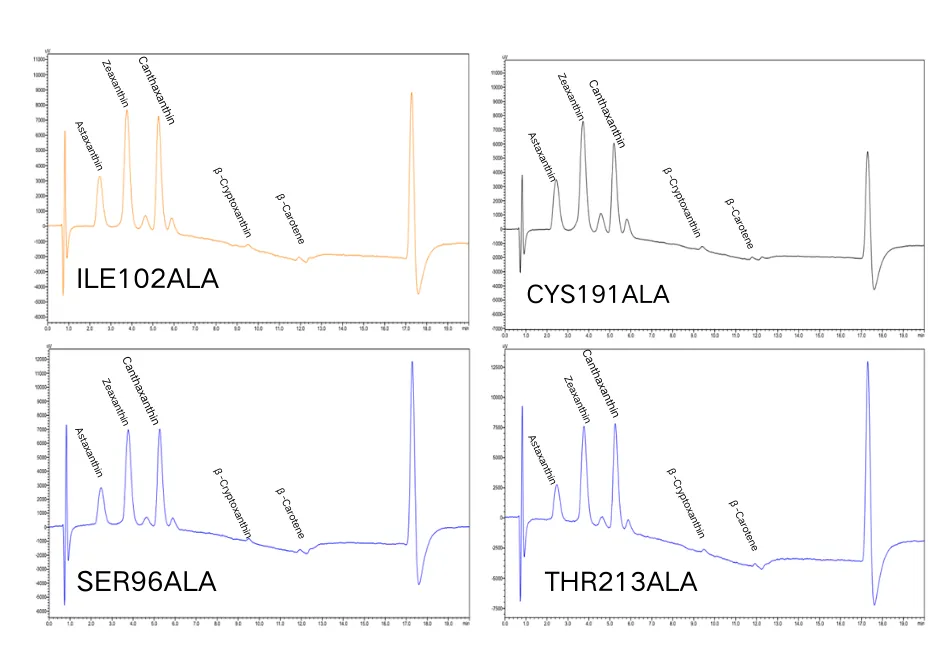

As shown in Figure 13, astaxanthin and its intermediates were detected in all mutants, but β-carotene was largely undetectable, indicating that most of the β-carotene had been converted into downstream products.

Figure 13. Analysis of astaxanthin and its intermediates from the mutants

Figure 13. Analysis of astaxanthin and its intermediates from the mutants

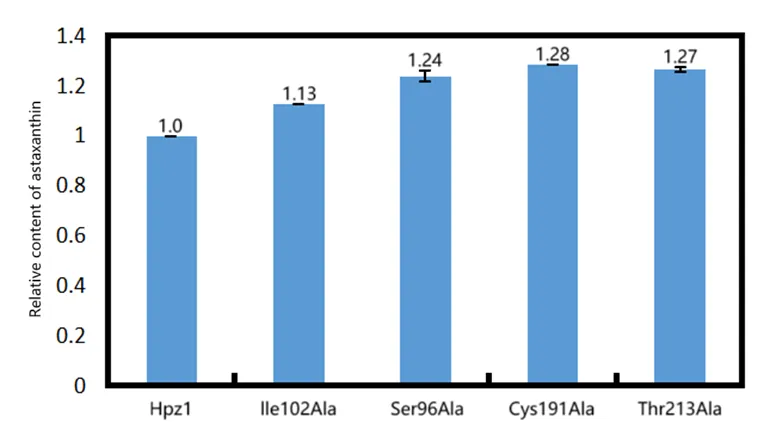

Figure 14 shows that the HpCrtZ and four mutants (ILE102ALA, SER96ALA, CYS191ALA, THR213ALA) were able to synthesize astaxanthin. Using the astaxanthin yield of HpCrtZ as a reference, the astaxanthin yields of the ILE102ALA, SER96ALA, CYS191ALA, and THR213ALA mutants were 1.13-fold, 1.24-fold, 1.28-fold, and 1.27-fold higher, respectively. Validation in E. coli confirmed that the rational design successfully enhanced HpCrtZ activity. All four mutants increased astaxanthin production, with the Cys191Ala variant yielding the highest titre at 1.28-fold that of the wild-type.

Figure 14. Effect of β-carotene hydroxylase alanine mutants on astaxanthin production

Figure 14. Effect of β-carotene hydroxylase alanine mutants on astaxanthin production

Based on the above experiments, we have drawn the following conclusions.

(1)We optimized the combination of astaxanthin synthesis genes through literature review and successfully produced astaxanthin in E. coli.

(2)Products analysis revealed significant accumulation of canthaxanthin, indicating insufficient activity of the β-carotene hydroxylase.

(3)Computational analysis and molecular docking identified four potential HpCrtZ mutants.

(4)Experiments validation confirmed that all four mutants enhanced astaxanthin production, with the HpCrtZ(Cys191Ala) variant yielding the highest increase of 1.28-fold.

However, the issue of possible toxin production when using E. coli as a production medium remains unresolved. Therefore, in subsequent experiments, we will explore the use of non-toxic microorganisms such as yeast for production [14-15]. In addition, we are exploring strategies to improve the competitiveness of our project in the existing mask market. By combining innovative biotechnological approaches with health and safety considerations, our astaxanthin face masks aim not only to be a more effective anti-ageing solution, but also to minimise potential health effects. The potential of our project to reduce wrinkles and protect facial health underscores our commitment to creating products that are healthier, more sustainable and safe for humans.

[1] Ito N, Seki S, Ueda F. The protective role of astaxanthin for UV-induced skin deterioration in healthy people: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Nutrients. 2018;10:817.

[2] Ouyang Z, et al. Production methods, biological activity and potential application prospects of astaxanthin. Foods. 2025;14:2103.

[3] Wang W, Li Y, Hu Z, et al. Genome mining of astaxanthin biosynthetic genes from Sphingomonas sp. ATCC 55669 for heterologous overproduction in E. coli. Biotechnol J. 2016;11:228–237.

[4] Ma T, Zhou Y, Li X, Zhu F, Cheng Y, Liu Y, Deng Z, Liu T. Genome mining of astaxanthin biosynthetic genes from Sphingomonas sp. ATCC 55669 for heterologous overproduction in E. coli. Biotechnol J. 2016;11:228–237.

[5] Huang D, Liu W, Li A, Wang C, Hu Z. Discovery of geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate synthase (GGPPS) paralogs from Haematococcus pluvialis based on Iso-Seq analysis and their function on astaxanthin biosynthesis. Mar Drugs. 2019;17:696.

[6] Shah MMR, Liang Y, Cheng J, Daroch M. Astaxanthin-producing green microalga Haematococcus pluvialis: from single cell to high value commercial products. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:531.

[7] CN109777820A. An engineered strain for astaxanthin synthesis and its construction method. 2019.

[8] Goodwin TW, Jamikorn M. Carotenoids of Chlorella. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1973;70:3240–3244.

[9] Zhou L, Wang Y, Li Z, Chen J, Xu Q, Liu H. Production of astaxanthin with high purity and activity based on metabolic engineering and fermentation optimization in E. coli. Process Biochem. 2025;118:1–11.

[10] Studier FW, Moffatt BA. Use of bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase to direct selective high-level expression of cloned genes. J Mol Biol. 1986;189:113–130.

[11] Terpe K. Overview of bacterial expression systems for heterologous protein production: from molecular and biochemical fundamentals to applications. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2006;72:211–222.

[12] Liu Y, Yang X, Gan J, Chen S, Xiao ZX, Cao Y. CB-Dock2: improved protein–ligand blind docking by integrating cavity detection, docking and homologous template fitting. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022;50:W159–W164.

[13] Van Petegem F, Duderstadt KE, Clark KA, Wang M, Minor DL Jr. Alanine-scanning mutagenesis defines a conserved energetic hotspot in the CaVα1 AID-CaVβ interaction site that is critical for channel modulation. Structure. 2008;16:280–294.

[14] U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Microorganisms & microbial-derived ingredients used in food: Partial list. 2022.

[15] EFSA Panel on Nutrition, Novel Foods and Food Allergens (NDA). Safety of astaxanthin for use as a novel food in food supplements. EFSA J. 2022;20:e07161.